Better Animated Feature: 2001

Did Shrek really deserve to win the inaugural Best Animated Feature award?

Preston: The Academy Awards are among the most prestigious given out in the field of entertainment—or, well, in anything, really. They’ve been going strong since 1929 and have handed out over three thousand Oscars, presiding over the recognition of excellence in film for nearly a century. And after resisting the inclusion of a category honoring non–live action movies for decades, the Academy finally elected to create one in 2001 as serious competitors to Disney’s preeminence emerged.

For a generation since, the award for Best Animated Feature has quickly become one of the most noteworthy presented at the Oscars, providing a space to acknowledge features that would otherwise only rarely receive so much as a nomination for Best Picture. It’s a great way for the Academy to acknowledge an often-disregarded medium of film, one which has produced some truly exceptional work across the last 23 years.

One slight problem: they kinda suck at picking it.1

That’s where we come in! We (that’s everyone at The Low Major, plus myself over at

, and probably a few other friends along the way) all happen to be pretty big fans of animation. Countless pundits have corrected the Academy’s homework on other notable awards, so why not do the same on one it seems to get wrong with remarkable frequency? I mean, seriously—Happy Feet over Cars in 2006 and Brave over Wreck-It Ralph in 2012? Not to mention the countless cases when an unobjectionable, unexceptional film beat out an instant classic (like 2005, when Howl’s Moving Castle lost to Wallace & Gromit: The Curse of the Were-Rabbit), a seemingly obvious contender was snubbed altogether (like 2014, when The Lego Movie didn’t get a nomination while The Boxtrolls did), or an utterly inexplicable film was nominated (like, well…2001, when Jimmy Neutron somehow made the list). Surely, we can do better.That’s what this series is about. Every two weeks, starting today, the day after 2023’s Academy Awards ceremony, and ending—for now—shortly before 2024’s, we’ll each take a look at one of the films that fell short and measure it against that year’s winner, then deliver a verdict on whether it was a better animated feature (hey, that’s the title of the series!) and should’ve won instead. You won’t see all of us every single year, but we’ll make sure to cover all the nominees, plus any deserving candidates that the Academy ignored entirely.

Without further ado, let’s get into 2001!

The early history of Best Animated Feature results coincided with the emergence of 3D animation, which was part of the reason the award was introduced in the first place. Many of Disney’s emergent competitors in the late 1990s and early 2000s set themselves apart with a variety of stylistic approaches, which makes a lot of these winners, nominees, and snubs difficult to compare. This diversity corresponded with significant victories for more niche animation styles; 2002’s Spirited Away, 2005’s Wallace & Gromit: The Curse of the Were-Rabbit, and 2006’s Happy Feet were all wins not just for smaller studios, but for animation styles aside from the distinct look more mainstream films quickly settled into. Most notably, of course, it led to a landmark win for DreamWorks’ Shrek—but was there anything better out there?

The Nominees

Shrek (won Best Animated Feature)

Jimmy Neutron: Boy Genius (nominated)

Monsters, Inc. (nominated)

Atlantis: The Lost Empire (snubbed)

Osmosis Jones (snubbed)

Waking Life (snubbed)

The “Best” Animated Feature: Shrek

Eli: If Pixar’s classic canon excels at being equally heartwarming to both children and adults, DreamWorks’ early works excel at being equally lowest-common-denominator.

The story of Shrek isn’t really original at all, both because it’s based on a book and because the book it’s based on is a fairly basic subversion of a fairytale. That satirical element excuses a good few hackneyed and sometimes outright nonsensical plot elements.

Shrek is also famously crude for a kids’ movie, and though these tropes are central to Shrek’s character and his budding romance with Fiona, their overuse tends to remove power from the theme of the story. If this movie was supposed to be played straight, it’d absolutely fail because it uses even its main moral message for gross-out gags and cheap laughs more than it does to tell a story.

And then there’s the soundtrack. For better or worse, DreamWorks is infamous for jamming their soundtracks chock full of pop songs and Shrek is patient zero. The selections here are iconic, to the point that “All-Star”, “Bad Reputation”, “I’m On My Way”, and “I’m a Believer” are still associated with Shrek by probably millions of people to this day. Their inclusion also likely served to make the movie more appealing to adults, as children like us wouldn’t have recognized most of these songs at the time, while adults probably knew and liked most of them. On the downside, this detracted from the film’s original score. Fiona’s motif—the song she sings as she blows up that poor bird—comes back several times for good reason, but the overuse of pop songs in the film is enough to make one question whether that number is also somehow a licensed track.

The visuals in this movie are a mixed bag. On the one hand, it’s painfully 2001 CGI. Outside of the opening sequence, the fluidity of the animation in Shrek pales in comparison to that of fellow Best Animated Feature nominee Monsters, Inc. But, on the other hand, Monsters, Inc. didn’t have believable human models, nor did anyone else in 2001. What DreamWorks did with Shrek in that department truly was marvelous.

But what really sets Shrek apart is the star-studded voice cast. It’s pretty funny that, more than a decade before Pixar sent Reese Witherspoon home for not doing a believable enough Scottish accent to voice Brave’s Merida, Mike Myers added a mediocre fake Scottish accent to Shrek and it fast-tracked him to being one of the most recognizable characters in the history of animation. The irreverence and joviality of the voice cast here are almost certainly what pushed the film to cultural icon status.

Was Shrek actually the best animated feature of 2001? We’ll be the judge of that. But it was certainly the most important. The groundbreaking feat of animating 3D humans that weren’t cartoonishly out of proportion was enough to win Shrek the award. Its willingness to be the butt of the joke pushed it over the top, allowed it to remain beloved by millions for years, and eventually landed it in the National Film Registry.

The Other Animated Features

Jimmy Neutron: Boy Genius — Eli

Nominated

I legitimately can't believe this film got a nomination.

Jimmy Neutron: Boy Genius is ugly to look at. The character models all look like plastic. The whole thing is animated like one of those shorts you see when you bowl a strike at the local lanes, made worse by the obvious glitches throughout the entirety of the 82-minute runtime.

The script is poorly written, including a deluge of humor so juvenile as to become unbearable, with few to no redeeming qualities for adults. It’s also poorly acted; multiple voice actors are reused for several different-sounding characters and almost none of them work, but the main cast is also mostly bad. And when you’re not listening to mediocre voice acting, your ears are graced with one of the most thoroughly mediocre scores and soundtracks in the history of film.

If you can somehow look past all that, your next task is to try to understand the point of the story. The message is muddled and I wasn’t even clear on what the primary conflict was until about halfway through the movie, likely because there are too many antagonists and it’s not immediately apparent which one of them is supposed to be the Big Bad.

Again, this thing isn’t even an hour and a half long—it’s the shortest movie we’re reviewing in this piece—but so much nonsense is jam packed into it that it feels so much longer. That would be a good thing in the hands of a better movie. Instead, I just feel like Jimmy Neutron wasted far more of my brainspace than it should have ever been allowed.

This obviously didn’t deserve to win any awards. I’m assuming some sort of starfuckery went on behind the scenes for it to receive one of just three Best Animated Feature nominations in a year when there were more than three great animated films and this wasn’t one of them. Perhaps the allure of even the worst 3D animation was just too hard to resist in the medium’s pioneering days.

The Mount Rushmore of Nicktoons in my childhood was SpongeBob SquarePants, The Fairly OddParents, Danny Phantom, and the series this film introduced: The Adventures of Jimmy Neutron, Boy Genius. With the benefit of hindsight, it’s pretty clear Jimmy Neutron was the worst of the four.

Verdict: Not a better animated feature

Monsters, Inc. — David

Nominated

Unlike Jimmy Neutron, I totally understand why this film got a nomination.

Made by industry titans Disney in the earlier days of their collaboration with Pixar (this was the fourth of nearly thirty films in the complete anthology), this embodies so much of what I would likely consider “award-fodder” these days—but it’s important to also remember that this is the first year of an award propagated almost entirely because of what Pixar had done for the world of animation.

We’ve spoken about this movie before through our Pixar Pints series, so I won’t wax too poetic on it, but there are some pretty fantastic moments within this that absolutely make it worth a nomination. The fur animation alone puts it within shouting distance, but there’s a lot of really strong acting, a good heartwarming plot to follow, and enough of a through-line for audiences of most ages to enjoy it.

This is arguably the movie with the best argument over 2001’s winner, Shrek, in terms of cultural impact, but even then, I think the scale tips in favor of the winner here. As much as Monsters, Inc. has had significant legacy, Shrek has to a greater degree (and largely done so without the massive heft of a supercorporation like Disney behind it, as massive as DreamWorks is in its own right).

Were I to make a case, I’d base it on this: Monsters, Inc. clears its moral better than Shrek. Where Shrek makes the case that appearances can be deceiving, it often does it with a satirical eye, and much of the movie is spent making cracks at characters for their appearances—accurate, but not exactly inspiring. Monsters, Inc. instead chooses to keep much of the plot passing in the same direction—as Sully and Mike work to foil Randall and Waternoose, Sully grapples with the ramifications of their discovery and how that impacts him and his past actions personally. It’s cleaner, certainly, but it doesn’t really ring clever.

Too many plot holes exist within this universe (things that I, even as a child, picked up on, things that have only raised more questions upon further investigation), and that’s one thing Shrek does pretty well: for all the flaws in presentation, it’s a really cut-and-dry story—a lesson that Pixar could have done well to learn from.

Verdict: Not a better animated feature

Atlantis: The Lost Empire — Preston

Snubbed

In 2001, before voters realized they could just throw votes to whatever Disney or Pixar put out in a given year, there wasn’t much clarity on the future of animated film, and the options for the first BAF had very little in common. Notably, though, all three nominees represented the rapidly growing field of 3D animation, which one could argue contributed to the corresponding decline of 2D animation. Disney’s major traditional release, Atlantis: The Lost Empire, was already a box-office failure, but missing out on a nomination here—while Pixar’s Monsters, Inc. earned one and rival DreamWorks’ Shrek ultimately took home the award—was certainly a factor in the studio’s shift away from this style, if not the decisive one. By 2005, Disney had largely transitioned away from 2D films, and they haven’t released one since 2011.

I have a bone to pick with the 2001 nominations because of this; it’s tragic that, in a single generation, this studio went from a legendary run of 2D masterpieces to its current era, where even Wish—a film designed as an homage to Disney’s history—couldn’t use 2D. But even setting aside the consequences of this inaugural award and its results, I still think Atlantis very clearly deserved a nomination at the very least. Released in competition with the shock blockbuster that was Shrek, it never really got the attention it deserved, but it’s on par with much of Disney’s iconic 1990s filmography.

Should it have won Best Animated Feature, though? I think that depends on what you want the award to represent. You could make an argument that cultural footprint is a factor here, in which case Shrek blows everything else out of the water; it spawned two multi-film series, is packed with memorable scenes, quotes, and characters, and remains one of the unlikeliest successes in movie history. You could also argue that it’s important to judge movies with regard to the standards for their medium, which definitely strengthens Shrek’s case—its weak points are either partly or completely a product of being a 3D film very early in the era of 3D film, and particularly early in DreamWorks’ forays into the field.

It was certainly more experimental than Atlantis, but honestly…I have a hard time calling it better. The character dynamics are painfully awkward until Fiona shows up nearly halfway into its runtime, and its core theme about appearances not mattering feels hollow when it can’t stop making jokes about the antagonist’s appearances. Atlantis is a safer movie in a lot of ways, not just in its approach to animation, but it tackles its story with the practiced excellence of a film studio that had long since perfected its formula. Almost every character is uniquely charming, and what the visual style lacks in technical ingenuity, it makes up for by being one of Disney’s best-looking 2D films from beginning to end.

It’s hard not to think Atlantis would get a much fuller and fairer look from today’s voters—not just because it’s a Disney film, but because its story is mature and nuanced in a way that many felt didn’t suit the medium of animation. (That kind of thinking still plagues the Academy’s opinions today, but 2002’s winner would very quickly make it a lot harder to claim openly.) Without making allowances for the context in which Atlantis and Shrek released, it’s not a close call at all, and while the circumstances make this film a much less clear winner, I still think it deserved the award.

Verdict: Better Animated Feature

Osmosis Jones — Nik

Snubbed

If the Academy Award for Best Animated Feature only took into account the animated parts of hybrid movies, Osmosis Jones may have actually gotten at least a nomination. The terribly acted live-action sequences cannot be overlooked, however.

The fictional universe the writers were able to create inside of Bill Murray’s character’s body is actually quite complex. Somehow, they were able to take the inner workings of the human body and make it into a society. There are some really creative references to the real world, including the umbilical cord being the Mayflower, and power lines being nerves. Someone who is a bit more versed on the human body may have issues with the exact science, but it is evident that it was thought out, and not just thrown together with basic knowledge of our innards.

While the live action sequences are necessary in order to drive the plot, they are slow-paced and filled with terrible characters. There is a sense of whiplash when changing to the live-action parts compared to the action-packed animated sequences.

Unlikable characters do not help either. Bill Murray plays a comically unhealthy and disgusting individual, and an even more disgusting father. The dynamics between him and his daughter do not work—he sits around all day while she waits on him and tries to schedule doctor’s appointments. At one point you even find out that the mom was equally unhealthy and that she died because both parents did not listen to their daughter —WTF!? There are bits throughout the film where you are kind of made to believe the dad wants to be a good dad. However, this character development is all for naught as the only thing that causes him to change is literally dying and coming back to life.

The worst part is that there was a TV show that came out after the movie that was purely animated, showing that the live-action is unnecessary for the movie to exist.

Again, the animated part of Osmosis Jones has a fantastic setting and fun characters. Remixes of popular songs on the soundtrack are a bit iffy but overall add a unique vibe. Even though the movie may have met the 75% animation threshold required to not be disqualified, it might as well have been, as this movie definitely deserves it’s 6.3 IMDb rating.

Verdict: Not a better animated feature

Waking Life — Leah

Snubbed

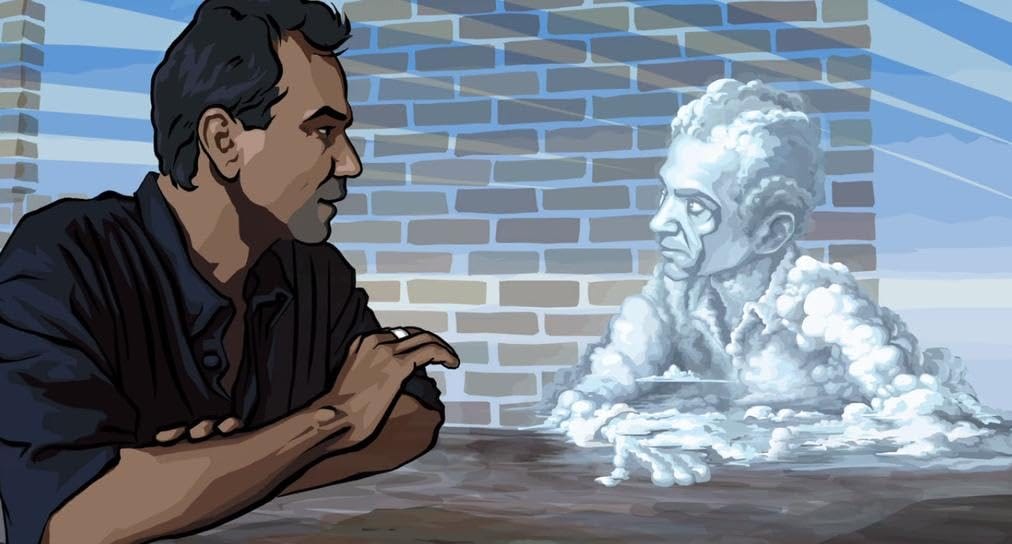

Waking Life should have been the Best Animated Feature of 2001. Using rotoscope animation, it shows a young man going through a series of dreams, replicating the surreal nature of dreaming that many of us have experienced, while also exploring different philosophical approaches to life.

At the very least, Waking Life should have gotten a nomination over Jimmy Neutron: Boy Genius. I’m honestly baffled at how that movie got the nomination over this. Maybe I should dream a conversation with the person who selected the nominees so I can try to understand their thought process. I would expect it to be about as off-the-wall as some of the scenes in Waking Life.

But going back to why this should have won the award over Shrek, Waking Life is more visually appealing, more thematically rich, and thought-provoking in a way that a movie like Shrek could never be. I should point out that comparing a movie like Waking Life to a movie like Shrek is like comparing an avant-garde novel I was assigned in a college literature class to a beloved children’s novel that I read over and over again in elementary school. Both have artistic merit for different reasons, but they don’t share much in common beyond the medium. Which movie is “better” will always be a subjective call, but based on what I got out of watching both films, Waking Life stands head and shoulders above.

Animation being relegated to a medium only for children does it a disservice, and this movie shows how it can be used to tell an adult story and visually support that story thematically. I’m a proponent of the avant-garde in art. It won’t connect with the majority of people, but I love the challenge that comes along with the experimental. The way this movie imitates the feeling of dreaming while exploring philosophy and different perspectives on life gives the viewer a chance to reflect on the ideas portrayed. And what more can we ask from art?

This movie should also be recognized for its technical achievements in rotoscoping. This was the first digitally-rotoscoped feature film. The visuals of this movie aged far better than the visuals of early CGI movies like Toy Story or Shrek. I want to recognize Bob Station for creating Rotoshop and the process of interpolated rotoscoping, and making this movie possible. Innovating in animation isn’t an easy task, and creating new ways to use the medium is worthy of celebration.

In conclusion, watch Waking Life. You’ll be treated to a surreal experience with unique visuals and thought-provoking scenes. You’ll also get to see a great technical achievement in rotoscoping, which I’m sure my fellow animation nerds can appreciate. This is a good film, and between the technical and artistic elements, there’s a strong case to be made that it is the best animated film of 2001.

Verdict: Better Animated Feature

Eli: So there you have it. Every movie that was nominated for Best Animated Feature in 2001 didn’t deserve to win, and most of the movies that weren’t did. I’m sure nobody will take any issue with this assessment.

Join us in two weeks when we compare Spirited Away, the first Hayao Miyazaki masterpiece to win this award, to the other four nominees from 2002: Ice Age, Lilo & Stitch, Spirit: Stallion of the Cimarron, and Treasure Planet.

See ya then!

Next: 2002

Editor’s note: this paragraph was written months ago and is not meant to be a jab at The Boy and the Heron or Hayao Miyazaki. —Eli

Waking Life WAS ROBBED