This post may be too long for email. We recommend clicking through to the website for the best experience.

Eli: From 1959 to 1966, the Boston Celtics won eight consecutive NBA titles. It’s the longest championship streak in the history of major North American professional sports. In my opinion, Pixar’s four straight Best Animated Feature wins from 2007 to 2010—forming the heart of their run of seven wins in ten years from 2003 to 2012—is even more impressive.

The Celtics at least have a rival; they have the most titles of all time (18), but the Minneapolis Lakers (who like to pretend they’re from Los Angeles) have just one fewer. Pixar has no match in this category. They’re in the middle of winning four Best Animated Feature awards in a row; meanwhile, at the time of this writing, no other studio has more than four wins, period.1

But enough sports metaphors—we’ve got seven movies to discuss and a new friend to welcome to the fray. Let’s get it started.

The Nominees

Up (won Best Animated Feature)

Coraline (nominated)

Fantastic Mr. Fox (nominated)

The Princess and the Frog (nominated)

The Secret of Kells (nominated)

Cloudy with a Chance of Meatballs (snubbed)

Ponyo (snubbed)

The “Best” Animated Feature: Up

Preston: Pixar’s golden age stretches across a pretty wide range of films. I think most people you ask would consider it to start right at the beginning with the iconic Toy Story (1995), though there are reasonable arguments for Toy Story 2 (1999) or Monsters, Inc. (2001) as well, depending on your tastes and how okay you are with A Bug’s Life (1998) being in the mix. In any case, by Monsters, Inc. it’s pretty obvious the studio is in peak form, and that continues through Finding Nemo, The Incredibles, Cars, Ratatouille, WALL-E, Up, and Toy Story 3 with barely a blip.

That’s a long time to be on top! In the estimation of the Letterboxd userbase, everything Pixar put out between 1999 and 2010 was at minimum a 3.7/5, a preposterously long run to set such a high floor. We’re getting to the end of it now, as the subsequent run of Cars 2–Brave–Monsters University firmly wrapped up this era and led into the less reliable Pixar of the 2010s, and it’s worth reflecting on just how long this studio had defined animation at this point.

2009’s Up marked Pixar’s third straight time winning Best Animated Feature, and they’d extend the streak to four with 2010’s Toy Story 3 before going on a drought of…well, one year, because Brave won BAF for some reason. As mentioned above, only one other studio—that of their parent company Disney—has won the award four times in total. Perhaps even more remarkably, Pixar has never failed to win Best Animated Feature in four consecutive years (though they’ll need Inside Out 2 to take it home for 2024 if they want to avoid the first such streak).

While the Academy’s decisions are far from perfect—I mean, hey, that’s the whole point of this series—this quartet of BAF winners pretty accurately reflects the point at which Pixar peaked. Going back to the Letterboxd consensus, these four films rank first, second, fifth, and ninth in Pixar’s catalog, and I think it’s fair to say they’re all considered among the studio’s true classics. We’re not nearly as high on Ratatouille, but otherwise there’s not much objection from us on that front: WALL-E averaged a 9/10 in the Pixar Pints series, while Up and Toy Story 3 both evened out to an 8.5. Ultimately, they landed eighth, ninth, and seventh in the AP Poll–style final ranking, and even Ratatouille earned a respectable tie for thirteenth. It’s an incredible stretch of film, whatever way you slice it.

Taking Toy Story 3 out of the picture, the Ratatouille/WALL-E/Up trio also stands out in another way. This group of films feels like a road Pixar explored, but decided not to go further down: the possibility of stylizing their films more in an effort to break out of the idea that animation was a medium for children. All three of these movies employ a prominent mid-century aesthetic in one way or another—it’s all over the place in Ratatouille’s depiction of Paris, it’s in the music (and, less obviously, in the retrofuturistic sci-fi) of WALL-E, and it’s most fundamental of all in Up, which is in part a love letter to adventure novels of the era.2

This stylization is one of a lot of little things that show just how much care was put into these movies, and such attention to detail is the reason I’ll die on the hill that WALL-E and Up are the absolute pinnacle of film. More than excellent in their own right, they were also hugely influential—a step beyond even what Pixar had done up to this point, which was already incredible in its own right. These are movies, with their meticulously crafted visual design and musical cues and character moments, that engage audiences of any age without sacrificing the studio’s youth-focused reputation. Pixar had been heading this direction for a while—The Incredibles was the first salvo in this delicate shift to a greater depth that remained approachable—and they perfected it here. So many subsequent animated films draw on that legacy, much of Pixar’s best modern work included, and I truly believe the fact that animation has gained so much respect is owed, more than anything, to what this studio did in 2008 and 2009.

Yes, the first fifteen minutes of Up are the best fifteen minutes of Up. There’s a reputation this movie has for delivering the most poignant opening in cinematic history and following it up with a story that could only ever be lesser. But who cares? It’s the tiniest of steps down, and that opening is only made more perfect by how the rest of the film follows it through. It’s hard to be upset about the tonal shift to more lighthearted drama and high adventure when those elements are pulled off so delightfully well, and the way they play into Carl’s character growth throughout the story couldn’t be richer. The start is an unparalleled 10/10—and in my eyes, so is the rest. For the second consecutive year, it’s an impossible act to follow and find a way to improve on.

That being said…2009 might be the best year in the history of animated film. So: did anybody do the impossible and one-up Up?

The Other Animated Features

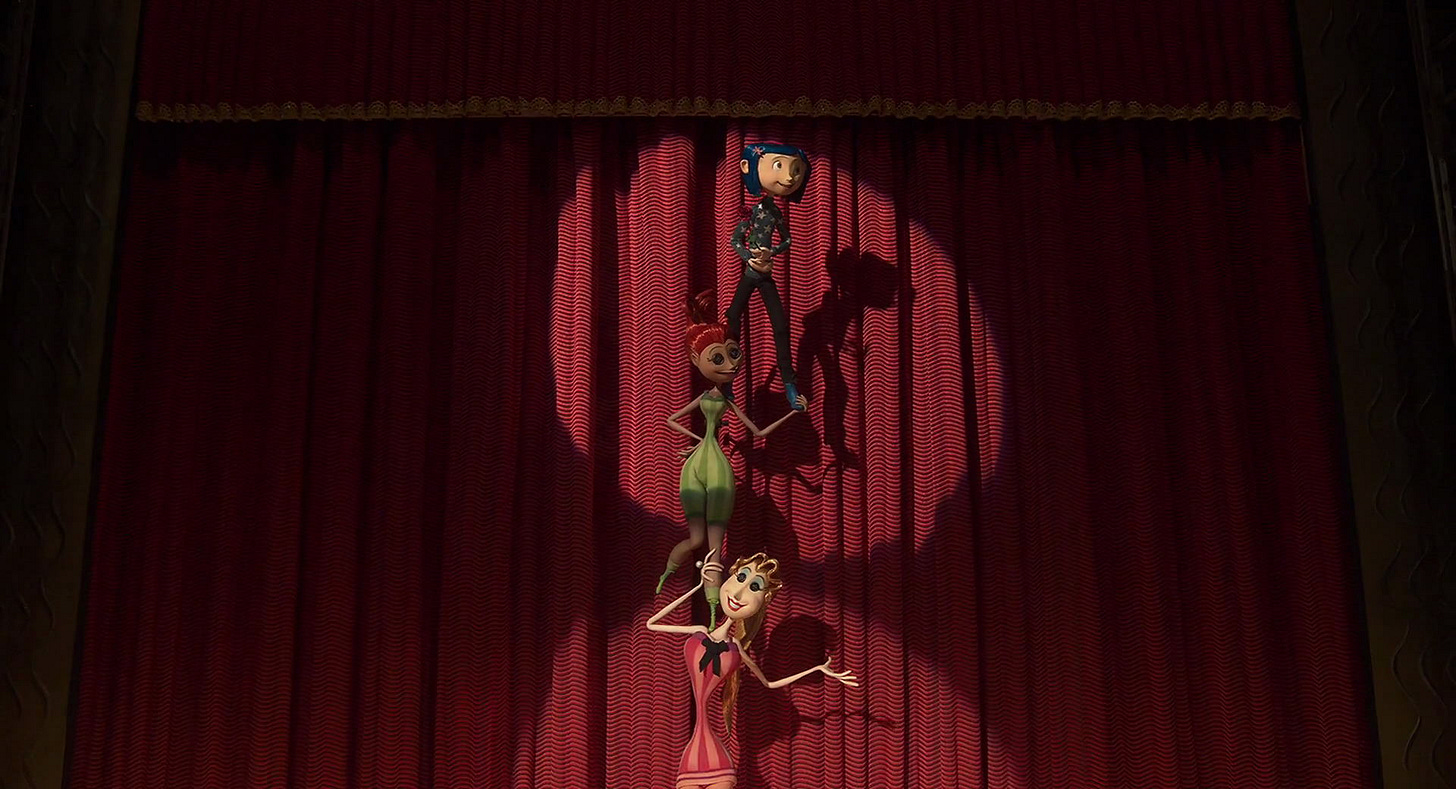

Coraline — Leah

Nominated

Coraline is a stop motion film adapted from the novella of the same name (written by prolific fantasy writer Neil Gaiman). It’s also the first feature-length film produced solely by stop motion studio LAIKA, a name we’ll see a lot from here on out, as all five of LAIKA’s feature films at the time of this writing have been nominated for Best Animated Feature.3

It follows the titular Coraline, a girl who has moved out to Oregon with her workaholic parents, who focus a lot on their writing for a gardening magazine and not very much on their daughter. Left to her own devices, Coraline finds a passage in her apartment to an alternate world with “Other” versions of her mother, father, and other characters. At first, it seems like she’ll get the happy life she desires in this world, but it takes a dark turn.

As LAIKA’s first feature-length film, Coraline sets the studio off to a strong start. It has a distinct style that expertly blends cartoony and creepy. The muted palette of Coraline’s ordinary life in Oregon contrasts with the vibrant colors of the other world, the character designs do a good job of conveying the characters’ personalities, and I’d be remiss not to mention the iconic button eyes and their uncanny effect. Coraline also pioneered using 3D printing to create the replacement faces for characters from the movie—an effective technique, as the characters were expressive throughout.

I’m glad I got a chance to watch a horror movie for kids that was actually good, and my only BAF horror experience wasn’t the worst movie I’ve had the displeasure of watching for this series (not to name names). Coraline has all of the elements of a quality film: a protagonist the audience can feel invested in, strong visuals that are both impressive and further the tone and narrative of the film, and, of course, a good story.

However, is that enough to make a case that it deserves a win over a film so well regarded and widely beloved as Up? Watching both movies, Up elicited the stronger emotional reaction from me. Carl’s arc was truly touching, and the story carried a lot of emotional weight. Not to say that Coraline’s struggles with her families and escaping the other world weren’t emotional or exciting, but I don’t think the resolution was quite as satisfying as Up’s.

Visually, I think Coraline was more interesting than Up. The art style is more unique (especially with the hindsight that writing this in 2024 affords me) and I think it does more the tone of the film than Up’s art style. The muted color palette of the real world, the intricate settings of the fantasy world, and the unique character designs come together to make something visually unique.

Musically, I think Up has the edge with its iconic leitmotif (though it doesn’t have a song by They Might Be Giants like Coraline does). The music in Up gives so much to the narrative and tone in a way few movie soundtracks do. Not to disparage Coraline’s soundtrack; Up’s just stuck with me more.

And, since I’m the one writing this review, I have to point out that Coraline had one clever talking cat, while Up had a whole pack of unclever talking dogs. Depending on your own biases, you’ll probably prefer one to the other; personally, I would take Coraline’s cat any day of the week.

2009 is a particularly difficult year to judge because so many of the nominees seemingly deserved to win. As the years go on, I’ll continue to run into this dilemma again and again: how do I treat a nominee that I think deserved to win the award when I think the original winner also deserved it? How should I treat my personal biases?

As always, if I think a case exists, I’ll do my best to make it. For Coraline, the case is that it’s a creative and innovative use of stop motion animation, an engaging narrative about escapism and the interpersonal difficulties of a young girl, and an outstanding first film from LAIKA. Meanwhile, Up won the award for its heartfelt story, technically impressive animation, gorgeous soundtrack, and well crafted narrative.

If you asked me which film I enjoy more, my answer would vary at different times in my life. Case in point: on this rewatch, I thought Up was the slightly better movie, but just two years ago, when we watched it for Pixar Pints, certain aspects (talking dogs) grated on me a lot more, while I didn’t appreciate other aspects (Carl’s emotional arc) quite as much.

I can’t definitively say which movie is better, but if I’m considering my feelings toward each movie at all points throughout my life, Coraline comes out ahead. Again, my goal for this series has always been to make the case for why someone might think one of the losers is better than the winner (if such a case exists), and I can understand why someone would vote for Coraline over Up. Ergo, I think this movie has enough going for it to call it a:

Verdict: Better Animated Feature

Fantastic Mr. Fox — Preston

Nominated

It feels weird trying to measure a Wes Anderson film against other Best Animated Feature contenders. Not necessarily because it’s better than them—as mentioned above, I think this year’s actual winner is basically perfect, and the rest of the field is unbelievably strong as well—but because Fantastic Mr. Fox is so different. I’m far from the first person to point out that Anderson’s style is absolutely unmistakable and distinct from anything you might try to compare it to, but…well, how can you not mention it?

In trying to weigh two vastly different films like these against one another, I often find that I’m driven to the attributes they have in common. The movies that have fascinated me most in this project are the ones that succeed at getting you in the mindset of a character who is fundamentally wrong, but still wanting them to change for the better. That’s a level of depth you see more and more throughout the 2000s, as animation develops into a more respected and widely contested medium, and these two films pull it off like almost no others.

That dissonance feels a bit different in Fantastic Mr. Fox, though, in a way that’s somewhat difficult to place precisely. In Up, you’re given some time after the opening sequence to learn that Carl has a lengthy character arc ahead of him. There’s a lot of genuine playfulness and adventurousness to his character, in sending Russell off after the nonexistent snipe and…well, y’know, tying a few thousand balloons to his house and flying away to Paradise Falls. It’s only when the circumstances change that it becomes clear how defined by the circumstances he is, and that character arc begins in earnest.

Fantastic Mr. Fox isn’t interested in winding its way around to its main character’s point. Like Carl, the titular Mr. Fox is set up as a free spirit who has to settle down into a domestic life, and his discontentment with his situation is what sets the story in motion after the establishing scenes. Unlike Carl, there’s no ambiguity whatsoever as to where his story is headed from these first post-intro moments. From the very first present-day scene, we’re told who he is and what he’s about—“I don’t want to live in a hole anymore. It makes me feel poor.” And Mrs. Fox is right there to tell us what we already probably suspect, and what the rest of the movie reminds us over and over again: this is a bad idea.

That’s the difference between Up and Fantastic Mr. Fox, beneath all the trappings that make them two very different films in a more practical sense. Up wants you to root for Carl; Fantastic Mr. Fox knows you’re going to root for Mr. Fox, and wants you not to, because you should and do know better. It’s blatantly clear that his overconfidence is going to land him in hot water through every beat of the story, and yet he’ll keep pushing his luck, and you’ll keep hoping that he can avoid having to grow into somebody a bit more mature and responsible. Anderson knows you can’t possibly watch a movie like this without cheering the main character on, and he uses every trick in the book to make that as uncomfortable as it should be, because nothing but the expectation of a classic lovable-rogue-versus-greedy-tyrants storyline suggests Mr. Fox should be cheered on.

The idea of this movie is spectacularly ambitious, and I’m not about to sit here and say it doesn’t follow through brilliantly. As attention-grabbing as Mr. Fox is (and has to be), there’s a ton more to adore about Fantastic Mr. Fox, and so much of it is executed to perfection. It’s a touching coming-of-age tale, a story about community, a remarkably delicate discussion of neurodivergence, and the best possible thing you can watch on a crisp autumn evening this side of Over the Garden Wall. I can’t say it’s absolutely perfect; there are a few clunky moments, most of them coming from the voice acting, which I’m afraid I’ll never quite get over with this film. And I can’t quite put it over Up for that reason—but I can say that, as was the case last year, there’s no shame in losing to this year’s actual winner.

Verdict: Not a better animated feature

The Princess and the Frog — Eli

Nominated

I’m gonna get one thing out of the way immediately: I’m not Black. I am The Low Major’s only contributor of color, but that color is a fairly light brown. If that fact disqualifies anything I could possibly have to say about this movie in your eyes, I completely understand. This will—spoilers—be a negative review, but I want to reiterate that if you, reader, like this movie and connect with it, then more power to you.

Personally, though, I think this movie is rotten to its core and doesn’t deserve to be mentioned in the same paragraph as Up, let alone the same shortlist. It’s bad in concept, not just in execution.

I kind of struggle to separate the botched minority representation from the botched Everything Else™. The best way I can think to put it is that all of the things that make this movie bad are made even worse by the fact that this is supposed to be specifically a Black story.

The movie takes place in and around Depression-era New Orleans, and the main characters spend most of the runtime with musical animals, but the soundtrack is among Disney’s most forgettable. That would be bad for any movie, but it’s especially disappointing for a movie that leans so heavily on the jazz music so deeply rooted in the era’s Black culture.

It’s a Disney Princess movie in which most of the narrative focus is placed on making sure the protagonist’s best friend feels like a princess, leaving the actual Disney Princess as a bit of an afterthought. That would break any movie, but it’s indefensible when your protagonist is a poor Black woman and her best friend is a rich white woman.

I feel out of my depth trying to explain all the ways this movie drops the ball. I sought out takes from a ton of people smarter and more personally connected than I, and as far as I can tell, opinions are mixed, but a lot of people feel the same way I do. For everyone’s sake, you should read them instead; here’s the one that stuck with me the most, from Harvard’s Kyla N. Golding.

Suffice it to say that I agree with this movie’s detractors. Not only is this movie obviously worse than Up—a classic that only gets better every time I watch it4—but I’d even go as far as saying it’s worse than every movie Pixar has ever released. Yes, even Cars 2, and yes, even The Good Dinosaur.

Verdict: Not a better animated feature

The Secret of Kells — Leah

Nominated

The Secret of Kells never had a prayer of winning Best Animated Feature. A small-budget film made outside the United States has never won in the past 23 years, and it might never happen. Which is a shame, because The Secret of Kells proves you don’t need a big corporate studio and tens of millions of dollars to make a truly great animated movie.

The Secret of Kells follows Brendan, a young monk living at the Abbey of Kells, who is fascinated by the work of illuminators.5 His uncle, the Abbot of Kells, is more concerned with building a wall to keep out the Northmen, a group of Vikings that have been terrorizing Ireland and bringing destruction in their quest for gold. Refugees from these attacks come to seek shelter at Kells, including Brother Aidan of Iona, a master illuminator, bringing the unfinished Book of Iona with him. Aidan encourages Brendan’s interest in illumination, eventually revealing that he wants Brendan to create the Chi-Rho page of the book (which will be the most intricate and important page). Brendan befriends a fairy named Aisling while going outside of Kells to gather berries to make ink. His uncle does not approve of him leaving Kells due to the danger posed by the Northmen, and thinks that focusing on building the wall is more important than creating manuscripts, ignoring Aidan’s warning that a wall will not be able to keep the Northmen out.

The Secret of Kells draws heavily from Irish culture for just about every aspect of the film. The Book of Kells is a real illuminated manuscript created in Ireland during the Middle Ages. Specific details about the creation of the Book of Kells are lost to time, but that leaves room to blend historical theories and Irish mythology into a compelling narrative about hope, adversity, and the importance of creativity and imagination. For instance, Pangur Bán—a real cat who was the subject of a famous Old Irish poem—made a fantastic animal sidekick for this movie. Visually, Irish culture greatly influenced the movie’s medieval art style. All in all, The Secret of Kells was made by people celebrating their culture and heritage, and it shows through every minute of the film.

I’ve adored this movie since I first watched it on Netflix when I was in high school. I was drawn in by the amazing art, and found the story to be both inspiring and touching. Feeling not good enough to create is an experience most artists have at one point or another in their artistic journey. Seeing Brendan overcome those doubts inspires me to overcome my own. Additionally, spreading hope in times of turbulence is an evergreen concept. I love how the movie shows the characters standing up to oppressive forces and refusing to stop the creation and dissemination of knowledge and culture.

I can’t fail to mention how gorgeous The Secret of Kells looks. In addition to the aforementioned Irish cultural nods and medieval setting, the backgrounds are pure works of art, and the way they animate the Book of Kells at the end of the movie is so cool!

Importantly, the character designs are also sleek and stylish, conveying a lot of personality. There is one exception here, though: the people of color, particularly Brother Assoua, are designed in an overly cartoonish manner to the point of being offensive. The directors of the movie wanted to reflect that the Book of Kells had been created by monks from all over the world, which is a good intention, but there’s really no excuse for those character designs, especially in 2009.6 I can’t blame anyone for being put off from the movie because of it.

It’s no secret that animation is expensive. Paying for the resources and expertise necessary to create a feature length film is always going to require money, and lots of it. Up had a budget of $175 million, The Princess and the Frog had a budget of $105 million, Coraline had a budget of $60 million, and Fantastic Mr. Fox had a budget of $40 million. All of those films looked good, and clearly it took a lot of money to achieve that. The Secret of Kells was in development since 1999, and it had a long road to get funding. Cartoon Saloon had to work on commercials and other more financially lucrative projects to keep the lights on, and it wasn’t until 2005 that the film really secured enough funding. They had a budget of 6 million euros (8 million USD), just 20% of the second lowest budget among 2009 Best Animated Feature nominees and a mere 4.6% of the budget for the winner.

If the Best Animated Feature award is intended to celebrate achievement, it’s worth noting how remarkable it is that a group of animation students managed to form a studio and spend a decade funding and creating their movie about celebrating Irish culture. It’s also outstanding that they made the most gorgeous looking animated movie of 2009 on by far the lowest budget of all the 2009 nominees. Pixar was a well established studio by then, in the middle of one of the most legendary runs in the history of cinema. It’s not surprising that they were able to come out with a big budget movie in 2009; yearly Pixar releases were standard by that point. It’s all the more impressive that the upstart Cartoon Saloon managed to release a gorgeous, artistically distinct movie with an inspiring story and intriguing lore.

Up is a really good movie, but I don’t think it quite has the same cultural significance as The Secret of Kells. The latter contributes something more unique to the world of art and animation (and I just enjoy looking at it more). The Secret of Kells is the first movie in the Irish Folklore trilogy, which—in my opinion—gets better with every movie. It’s a fantastic first film from a studio that will go on to make even more fantastic films. And the fact that they did so much with so little makes it even more spectacular.

It probably shouldn’t come a surprise that this is one of my favorite animated movies. What The Secret of Kells accomplished makes it a Better Animated Feature than Up.

Verdict: Better Animated Feature

Cloudy with a Chance of Meatballs — Olivia

Snubbed

It had been probably close to a decade since I’d seen Cloudy with a Chance of Meatballs. Still, I’d watched it several times as a kid, and I thought I knew it pretty well, so I went into this adult rewatch having a pretty clear idea of what my expectations were. I knew it was a fun, goofy movie with some pretty clever humor; and it is. What I was not expecting, and what completely flew over my head as a kid, was a shockingly mature commentary on neurodivergence and how it’s treated in society.

Before we get to that, though, let’s start with a fun fact. Did you know Cloudy with a Chance of Meatballs is actually based on a book? If not, now you do! Written by Judi Barrett and illustrated by her ex-husband Ron, the children’s story was told with the framing of a grandfather telling a story to his young grandchildren—in it, the people of Chewandswallow: where food naturally falls from the sky. Life was good, but eventually the food got too big for the people to handle and they sailed away on boats made of bread. The story is overall pretty bare-bones and, outside of a number of visual references, the movie doesn’t follow it almost at all. But my mother owned the book as a kid and then passed it down to me, so this is a story I have a pretty deep personal connection to from the start.

With that out of the way, let’s talk about the movie. Cloudy with a Chance of Meatballs was made by Sony Pictures Animation, which was mostly known for making a bunch of mediocre animated movies (did anyone really ask for four Open Season films?) before they were like “haha, joke’s on you, we actually know how to make amazing films” and dropped the first Spider-Verse movie in 2018. But among that fairly forgettable early filmography (sorry, I’ve heard Surf’s Up is good but haven’t watched it myself) lies Cloudy with a Chance of Meatballs, which in my mind is truly a diamond in the rough.

Cloudy with a Chance of Meatballs is about a young inventor named Flint, who’s always been a failure until one day he invents a machine to turn water into food. It starts creating food weather, which is a good thing at first until shit goes downhill and Flint and his friends have to fly up and destroy the machine to save everyone. In terms of plot, it’s fairly standard fare for a kids’ movie. But a few things elevate it to another level.

First, the humor. Y’all, I don’t know if it’s just my bar for humor being in the ground, but I genuinely find so many of the jokes in this movie hilarious. There are tons of great visual gags, and a lot of very quotable jokes as well.7 I legitimately reference the Officer Earl “I’ve got my eye on you” bit in real life occasionally, and rewatching the film for this review, I caught quite a few jokes I hadn’t remembered that I found just as funny. The British reporter translating “à la mode” genuinely destroyed me.

But, as I alluded to at the start of this review, the aspect of this film that really captivated me rewatching it as an adult was its portrayal of neurodivergence. As someone not technically diagnosed with anything in particular but nonetheless very obviously neurodivergent, I found several moments in the film’s intro painfully reminiscent of my own childhood. Being the “weird kid”, not fitting in with your peers, being clueless in social situations, making bad decisions due to the pressure of seeming to finally have the chance to be accepted by your peers. And the backstory of Sam Sparks, meteorologist and the co-lead of the film, comes from a different angle but is equally impactful. The way she’s pressured into masking her true personality to be seen as more presentable, not so “nerdy”. It’s a story that’s all too familiar to myself and many others.

“Have you ever felt like you were a little bit different? Like you had something unique to offer the world, if you could just get people to see it. Then you know exactly how it felt to be me.”

Admittedly, the movie doesn’t exactly have some super deep message on this topic. But it presents clearly neurodivergent characters in a very positive light, and over the course of the film they begin to accept themselves more, and be more naturally themselves. And that’s something I genuinely love to see.

The film’s other main theme, that of fatherhood and pride, is equally heartwarming. I won’t go into too many words about this one because this review is getting way too long, but the contrast between Officer Earl, who initially seems like just a comic relief character (and is a great one at that; Mr. T absolutely rocks the voice acting here) but whose main character trait turns out to be his love for his son, and Flint’s dad, who feels a similar love but doesn’t know how to express it, is another great piece of the emotional heart of this movie.

So now that I’ve written almost a thousand words gushing about this movie, you’d think this is the part where I say that it was a massive snub and deserved the Oscar, right?

Well, it’s not that simple. 2009 was a genuinely fantastic year for animated movies, to the point that popular YouTube channel Schaffrillas Productions made a whole video calling it “the year that animated films peaked.” I definitely think Cloudy with a Chance of Meatballs deserved a nomination, although I can’t really say for sure which of the nominees I’d swap out for it (probably The Princess and the Frog).

But let’s be real. Cloudy with a Chance of Meatballs is a movie I adore and appreciate, but it’s not Up. Up had the Oscar won about 10 minutes in, and it’s entirely deserved in my opinion. No matter how good you are, sometimes you’ve just gotta admit when you’re beat.

Verdict: Not a better animated feature

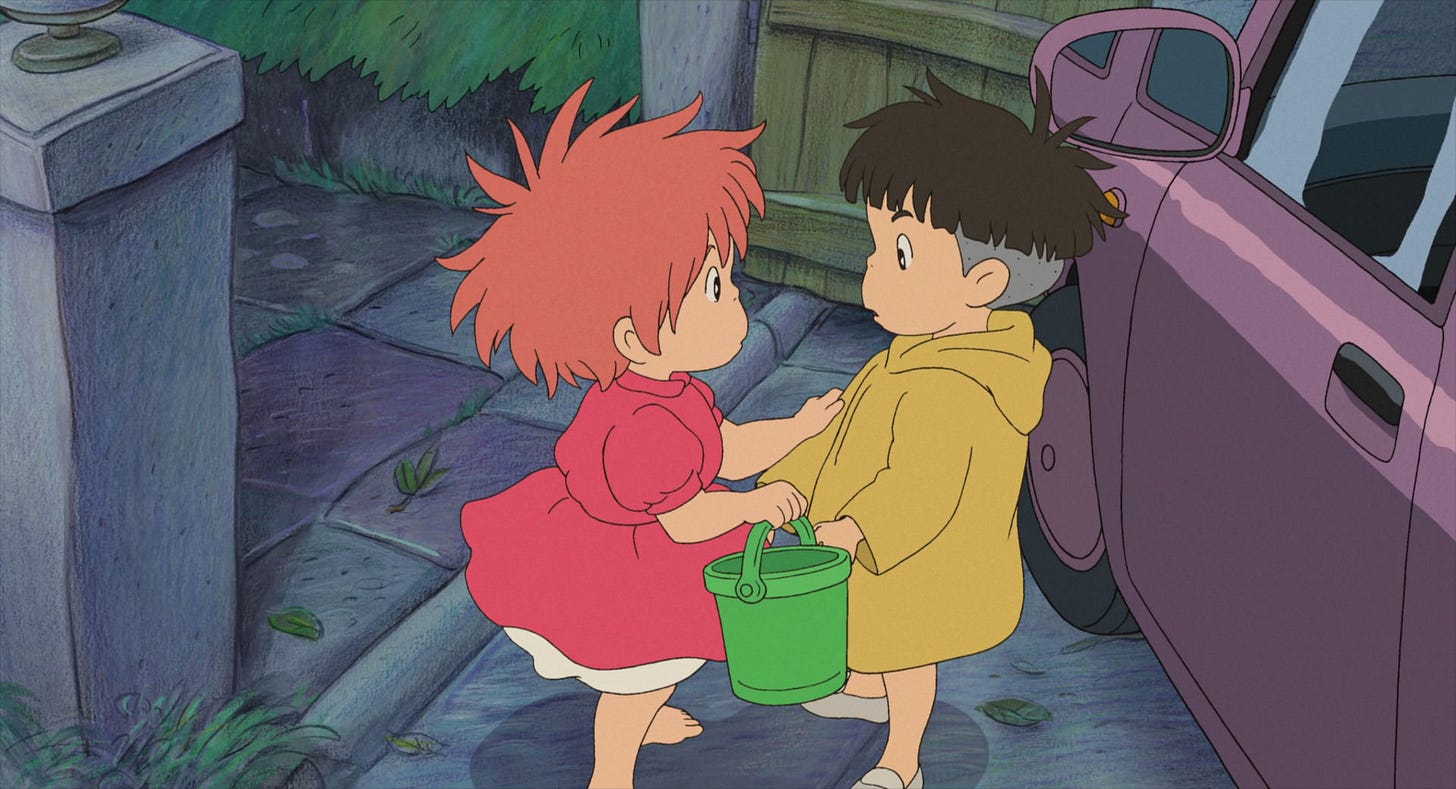

Ponyo — Preston

Snubbed

Studio Ghibli films tend to run a range from magical to slice-of-life, and as much as I can understand the admiration people have for those at the former end of the spectrum, the latter tends to be where my favorite works in their catalog fall. Even in their most fantastical movies, Ghibli just has an inimitable knack for capturing the subtlety and beauty of everyday life. Those moments really get to shine in more down-to-earth films like Whisper of the Heart and From Up on Poppy Hill, and it’s no surprise that those are among my inner-circle favorites.

Ponyo is an interesting case because, objectively, it’s very much on the whimsical, unreal side of things. The stakes are toweringly, terrifyingly high, and while the setting is more or less modern, it’s also got more than enough magic that it’s clearly a step away from most of Ghibli’s slice-of-life fare. Yet at the same time, when this movie shines most is when it boils down to little, human moments. There is some dazzlingly beautiful and cosmically terrifying imagery of the sort only Ghibli can capture so perfectly, but when it comes down to it, the scenes that stick with you are so entirely ordinary. I rewatch this movie for Lisa’s terrible driving and Sōsuke flashing the signal lamp to his dad and Ponyo tasting ramen for the first time. The fact that the world very nearly ends in the background makes for some fun scene setting and gives the plot some direction, but it’s not the real emotional thrust of the story.

This dramatic contrast always leaves me a bit conflicted about whether Ponyo is the best version of itself—which I think is a good question to ask if you’re debating whether a film is a 10/10 or a 9/10. And this film is absolutely strong enough to raise that question; it may be a little disjointed and have one or two many ideas going on, but for sheer heart it’s impossible to beat. Even among the more grounded, intimate films Ghibli has made, this one really stands out; not a moment is wasted without more characterization to flesh out the main cast. As unsteady as it arguably is in other ways, it’s still a very easy movie to love because you walk away from it adoring every one of its characters.

Ultimately, though, I end up falling on the 9/10 side, because Ponyo wants so much to be a movie with a much grander scope. There are so many plot threads and themes—love, humanity, family, responsibility, climate change—that tangle together in a way that makes it impossible to cleanly resolve them all. The ending is among Ghibli’s most ambiguous and confusing, and it really seems like it’s just because nobody quite knew what the film should actually have been about. The idea of a very mundane, endearing tale against a backdrop of high drama isn’t a bad one, but the studio’s executed it better before.8 Ponyo’s uncertainty about what it wants to be is the flaw that leads to it falling short of perfection, and the flaw that keeps it from toppling Up as my favorite of 2009’s stacked field.

Verdict: Not a better animated feature

Running Tally

2001: 2 better (2 nominated; 3 snubbed)

2002: 1 better (4 nominated; 0 snubbed)

2003: 1 better (2 nominated; 2 snubbed)

2004: 0 better (2 nominated; 1 snubbed)

2005: 2 better (2 nominated; 2 snubbed)

2006: 3 better (2 nominated; 2 snubbed)

2007: 3 better (2 nominated; 1 snubbed)

2008: 0 better (2 nominated; 0 snubbed)

2009: 2 better (4 nominated; 2 snubbed)

TOTAL: 14 better (22 nominated; 13 snubbed)

The Pixar will continue until morale improves: Toy Story 3 is on deck in 2010.

Next: 2010 (2 nominated; 4 snubbed)

Walt Disney Animation Studios has exactly four wins (all of which have come since Pixar’s decade-long run of dominance). Even UCLA’s seven consecutive men’s basketball titles from 1967 to 1973—widely counted among the most dominant runs in the history of organized sports—do not match Kentucky’s eight all-time titles.

Funnily enough, none of these films are even set before the turn of the 21st century—Ratatouille and Up canonically take place around their release years, and WALL-E is obviously set nearly a millennium into the future.

All six if you count 2005’s Corpse Bride, which was a co-production between LAIKA and Tim Burton Productions.

It was the highest of my 8/10 ratings during Pixar Pints, but when I rewatched it for this series, it became clear to me pretty early on that I underrated it. It’d get a 9/10 from me today.

Someone who creates an illuminated manuscript (such as the Book of Kells) [Editor’s note: better that than someone who creates an Illumination movie] —Eli

Here’s a screenshot of a now-deleted tweet from director Tomm Moore responding to criticism of Brother Assoua’s design.

Editor’s note: Flint, you, have a call! Flint you have a call! —Eli

I’m obligated to name Kiki’s Delivery Service, possibly my favorite film of all time, as a fantastic example of this. I’m also obligated to name Spirited Away, because it’s also a fantastic example, and also because I’ll get yelled at in the comments if I don’t.