Better Animated Feature: 2015

There's a reason Inside Out 2 grossed a gazillion dollars this year.

This post may be too long for email. We recommend clicking through to the website for the best experience.

Eli: 2015 is among the most obscure slates of nominees for this award. Aside from Inside Out—the only nominee from a major Hollywood studio—the general American audience could be excused for being mostly or entirely unfamiliar with every film on the shortlist.

But, y’know, I had never heard of Emotion by Carly Rae Jepsen until 2015 was already over, and it’s definitely my favorite album of the year, if not the entire decade. So perhaps one of the more obscure entries on this year’s slate has a “Run Away With Me” up its sleeve.

Shall we?

The Nominees

Inside Out (won Best Animated Feature)

Anomalisa (nominated)

Boy and the World (nominated)

Shaun the Sheep Movie (nominated)

When Marnie Was There (nominated)

The “Best” Animated Feature: Inside Out

Preston: I never really know how to feel about this movie. It’s got problems beyond just the plot—pretty messy and contrived in places, but that pretty much works for me given that most of the story is in someone’s head. The bigger problem to me is that they’re trying to juggle the plot, the core themes and messages, and a semi-accurate (if simplified) portrayal of how emotions actually work, and there are a lot of points where you just can’t get all three to work at once. You end up with stuff like the dinner argument scene, which seems super accurate on the face of it but also…has nothing to do with why a kid like Riley would actually be upset, and portrays her frustration as an irrational, completely anomalous episode. An eleven-year-old watching it wouldn’t see any connection to their own moments of impulsiveness and anger; arguably, they’d just feel more misunderstood. (Speaking as someone who was around that age when Inside Out came out, I should know.)

And yeah, despite all that, it is still a pretty darn good movie. Everything they’re trying works to a certain extent, and the sheer creativity of the setting is absolutely sensational; I’ve watched a lot of Pixar and not all of their worlds still manage to blow me away, but this one absolutely does. And as imperfect as it is, it’s still a very heartfelt story, one that serves as a great starting point for both kids and adults to understand that it’s healthy to feel and express whatever’s going on in your mind. It’s probably my favorite message in a Pixar film—a lot of their stories do have pretty simple and inoffensive themes, and this after Monsters University represents the biggest strides they've ever made towards getting at more complex and non-obvious morals.

Inside Out is not perfect; far from it. But it’s hard not to appreciate how ambitious this film is—not just in its creative scope, but also in the story it’s trying to tell. In a year when other major releases were limited to The Good Dinosaur, Home, and Minions, that made it an easy pick for the Academy when it came to this award. In a field of nominees featuring an R-rated stop motion comedy-drama, a largely hand-drawn Brazilian coming-of-age tale, an adventurous Aardman spin-off, and a Studio Ghibli psychological drama, did any of the long shots deserve more of a chance?

The Other Animated Features

Anomalisa — Eli

Nominated

Y’know, when I decided to take on this project, I didn’t really think I’d ever have to wade into the “film bro” discourse. As I mentioned a few weeks ago in my Rango review, it’s pretty rare that animated films are creatively led by live-action directors. It’s even rarer that a serious auteur turns to animation to produce an unmistakably adult art film.

But that’s what Charlie Kaufman did, and the result is Anomalisa. Sifting through reviews for this movie, so many of them go into how this affects Kaufman’s legacy or why he’s great or why he stinks, referencing other films he’s written or directed for comparison. And I just can’t do that because I haven’t seen Being John Malkovich or Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind or Synecdoche, New York and I simply don’t want to. I’m not a film bro; I’m an animation enby. Please keep that in mind when reading this review.

Anomalisa is a stop-motion psychological dramedy adopted from a 2005 “sound play”1 of the same name. It follows customer service expert Michael Stone on a business trip to Cincinnati, where he is scheduled to be a keynote speaker at a conference. Michael perceives everyone else—from his ex-lover to the hotel bellhop—as having the same facial structure and the same voice. But then he meets Lisa, a fan of his who’s also in town for the conference, and her face and voice immediately stand out to him as beautiful.

It’s kind of impossible to synopsize Anomalisa without summarizing almost every minute plot point. So many things that happen in this movie are incomprehensible without the context of a seemingly unrelated event, and all of this information is necessary to interpret Kaufman’s main point. Here are three things that happen in this movie, in the order that they happen, all of which directly connect with each other and cannot be explained without the other two (and dozens more):

Michael becomes annoyed at how chatty his taxi driver is on the ride from the airport to the hotel.

Michael goes off-script during his keynote speech and calls George W. Bush a war criminal.

Michael returns home and gifts a singing, animatronic sex doll to his elementary-aged son, who notices a white fluid oozing out of it and asks why it’s doing that, to which Michael’s wife nonchalantly replies that it’s semen.

You see what I mean?

At the end of the day, the whole point of this thing is that Michael is a deeply messed-up human being whose lack of ability to accept other humans as unique individuals has ruined his life. And, try as I might, I just can’t glean any value in the real world from the tale that takes place on-screen. I’m not a middle-aged, depressed, isolated horndog who feels compelled to cheat on his wife. Though these feelings—and reality itself—are captured extraordinarily well, the film just doesn’t say anything to me.

I can comment on the animation and, well…you can tell this was led by someone who isn’t usually an animator. Duke Johnson, the artist behind the stop-motion Christmas episode of Community, is listed as a co-director here, but this is Kaufman’s brainchild. Kaufman said straight-up that he wanted the viewers to forget they were watching animation in the first place, which is readily apparent because…the animation more or less serves no purpose? Stop-motion does a decent job of throwing the aesthetic straight into the uncanny valley, which does single-handedly add to the experience of this human-but-not-quite-human story, but aside from most characters having almost identical faces, there are very few effects in the 90-minute runtime that would be difficult to achieve in live action.2 Pretty much all of them happen in this wacky dream sequence toward the end, the most noteworthy of them being Michael’s face falling off as he realizes that he lives an empty shell of a life, which…is a child’s idea of what qualifies as groundbreaking symbolism in animation. Woody’s nightmare sequence in Toy Story 2 was deeper than this.

Trying to find any direct comparison between this and Inside Out is inherently hilarious: Anomalisa has an explicit sex scene3 and is the first R-rated nominee in the history of Best Animated Feature,4 while the most mature thing to happen in Inside Out is the “death” of an imaginary friend created by a toddler. But that comparison is what I signed up for, so I guess I’ll at least try.

Both movies are written pretty poorly as far as I’m concerned, but in Anomalisa’s case, that appears to be on purpose, so…partial credit, I guess? Both movies are, broadly speaking, about deconstructing the inner workings of one human’s brain, but they go about this task in extremely different fashions. And it’s in the differences where Inside Out stands out to me as the superior film. While Anomalisa lets the lack of flashy animation set a more realistic scene that allows the viewer to more thoroughly embody Michael, the way Inside Out envisions the mind through vivid animation is so outstanding that it almost escapes words (though I tried my best a couple years ago in Pixar Pints, linked above).

I don’t even love Inside Out. I gave it a 7/10 during Pixar Pints, well below critical consensus, and this most recent watch did not change that opinion—to say nothing of the sequel being superior in almost every way. When I started writing this piece, I thought I would be declaring Anomalisa the superior film. Funny how actually putting your thoughts on paper can shake things up.

Verdict: Not a better animated feature

Boy and the World — Leah

Nominated

Boy and the World tells a touching story of a young boy named Cuca searching the world for his father. A film with next to no dialogue, the visuals and the music carry the narrative and make the viewing experience. This film is unique among Best Animated Feature nominees in general, so let’s get into what sets it apart.

The art style takes inspiration from the drawings of children, stylized to create a stunning portrayal of the world from the view of a child. Make no mistake, even if the main character looks like a stick figure, a lot of artistic talent went into putting these visuals to screen. Watching this film will treat you to a world of color. Boy and the World makes good use of its visual symbolism with its portrayals of both the abstract and the recognizable. I can’t say any other BAF nominee looks quite like this one.

The narrative of the movie is also strong. Like I said, there’s little dialogue in the film (and the dialogue that is there is backwards Portuguese), but that doesn’t hold it back. In animation, the aspects of acting that don’t involve voice are up to the artists creating the film. The way a character is drawn and animated is integral to the performance, and this movie does a great job making these characters perform. The viewer can see the hope, the fear, the sadness, and the whole spectrum of emotions. Even in the film’s more abstract or metaphorical moments, the emotion of the story comes through. Also, without spoiling the film, the ending makes the viewer reconsider and recontextualize everything they’ve watched before it, in a way that makes the experience of watching the film even richer.

I also want to praise Boy and the World’s soundtrack. My favorite track is “Airgela”, which works well to set the tone of a specific scene in the movie and represent the characters. With little dialogue, music also does a lot of heavy lifting for the narrative and mood of the film.

Of course, is this enough to argue Boy and the World over Inside Out? The former is very much about exploring the outside world and interacting with it, while the latter focuses on the interiority of the human mind, personifying emotions and the relationships between them. When considering the art of Inside Out, it’s clearly some of Pixar’s best work, a truly imaginative representation of the human mind. However, Boy and the World is also an artistically imaginative film, albeit in a different way.

Inside Out’s narrative draws criticisms for being unclear conceptually. Boy and the World is more abstract than Inside Out, but I think that works in its favor. The emotions being concrete characters alongside Riley leads to some confusion over how the story is being driven. Boy and the World doesn’t have that problem.

I think this ends up being a textbook case of Leah saying that the movie you think deserved the award will ultimately come down to personal taste. Do you enjoy the interiority of Inside Out more or the way Boy and the World situates the self within society? Do you prefer the CGI-rendered representation of the mind, or the traditionally rendered representation of the world? Do you prefer the story of emotions impacting a young girl’s life or the story of the external world impacting a young boy’s life? Thematically and artistically, I think Boy and the World has enough going for it to be considered a:

Verdict: Better Animated Feature

Shaun the Sheep Movie — Preston

Nominated

As somebody who hasn’t seen anything by Aardman Animations after Shaun the Sheep Movie—neither 2018’s Early Man nor 2023’s Chicken Run: Dawn of the Nugget nor the 2020 sequel to this film, Farmageddon—I’m not the best person to ask if their quality has dipped. But I can say that of the studio’s entire feature-length filmography, the former two films in that list are the lowest-rated they’ve ever put out, and even the more popular Farmageddon doesn’t sit much higher. After winning Best Animated Feature in 2005 with Wallace & Gromit: The Curse of the Were-Rabbit and earning further nominations in 2013 and 2016, they’ve only earned one nomination since (and that was largely because 2020’s COVID-affected field was unusually short on worthwhile candidates).

I can say, though, that Shaun the Sheep Movie marks the definitive end of a long string of box-office successes for the studio. Starting with Chicken Run, their film debut in 2000, Aardman recouped over $100 million on its first six movies and turned significant profits on all of them. But Early Man took in just over its budget of $50 million, Farmageddon didn’t even make that, and Dawn of the Nugget went straight to streaming after theatrical releases of every prior film the studio had made. Their recent lack of Oscar buzz probably has as much to do with their decline in prominence as anything—they’re now merely one of many stylistically off-beat challengers to prominent, traditional 3D studios like Pixar, DreamWorks, and Disney, not the big outsider shaking the genre up.

I bring all of this up because, as it happens, we’re only a few months away from Aardman’s next release. Vengeance Most Fowl follows up The Curse of the Were-Rabbit, marking the third straight sequel to one of their most successful earlier films, and it’s in the running for a BAF nomination, one it has a pretty solid chance of picking up.56 I really hope it’s good enough to earn it—because, as Shaun the Sheep Movie serves as a great reminder of, Aardman’s work is among the most delightful in the film industry when they’re on their game.

This might be my favorite film of theirs. At the very least, it clearly (if narrowly) clears The Curse of the Were-Rabbit and The Pirates! Band of Misfits, the other two Aardman movies I’ve watched for this project, because the emotional arc of the story has finally been given the thought and attention it needs to really make everything click. Notably, they pull this off entirely without intelligible dialogue; the closest they get to that is a remarkably touching musical sequence that you can kind of expect to show up sooner or later from the very first scene, but which still tugs the heartstrings with surprising strength. Sure, a lot of the film is the typical visual gags and slapstick comedy you’d expect (and it’s as good as ever, because you can always know Aardman will give you that), but there are genuine, meaningful character arcs in there, too, and well-written ones. From Were-Rabbit lacking much in the way of character development at all and The Pirates! struggling to sell its emotional beats convincingly, they’ve come an awful long way.

Is this the Best Animated Feature of 2015? Eh, not quite. I really like Inside Out, all the more after rewatching it for this article, and while I love this film too, I have to admit that that film’s main trio works just a little better than this one’s. Being able to deliver actual lines of dialogue goes a long way there, and while it’s a stylistic choice you absolutely can’t fault this movie for, it does limit everything just a little in the end. Only a little, though; if this truly was the end of Aardman’s golden age, it’s a fittingly high note to go out on.

Verdict: Not a better animated feature

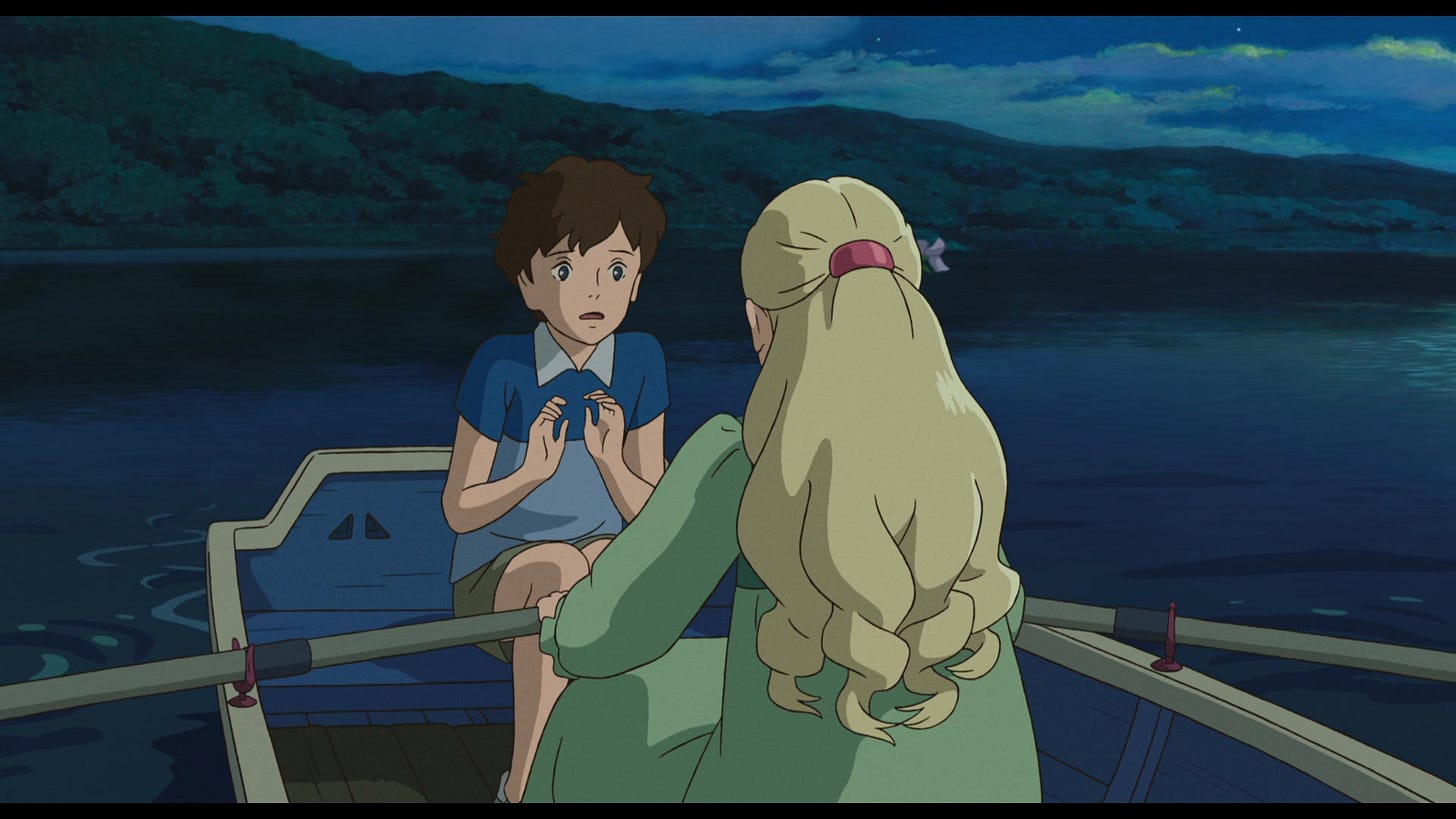

When Marnie Was There — Preston

Nominated

I’ve spoken before about the importance of adjusting expectations for what a film is trying to be when weighing up just how good it is. Pixar at their peak and Aardman at their peak, for example, are two very different things, and what constitutes excellence in each case will depend on different things. It’s important, to an extent, not to favor one movie over another because it hones in on certain things that just aren’t another studio’s forte.

But, of course, there’s value in ambition. Everybody’s standard for how this should all be weighed up is different—it’s hard to reward complexity without punishing intentional simplicity, and both have value in their own ways—but I’ll admit I do have some bias towards more involved stories. Inside Out and Shaun the Sheep Movie are both films that have two or three really developed characters and a supporting cast that mostly serves for plot progression and comic relief; in that light, When Marnie Was There stands out quite a lot.

The core of the story is obviously the relationship between Anna and Marnie, which is worthy of plenty of analysis on its own—but the film really shines because the cast as a whole is so incredibly rich. It’s among the broadest ensembles Ghibli has rolled out for a film, and they all get a chance to shine while also informing Anna’s arc.

If there’s a criticism to be given here, it’s that the film sometimes loses itself a bit too fully in developing Anna and Marnie, to the detriment of the more “real” side of the story. Obviously that pair is worth developing, given how much depth it takes on, but to me the most impressive thing about When Marnie Was There is how much Anna’s character is fleshed out, and I wish we got a little more variety in her relationships instead of focusing on one quite so intently. She’s written with remarkable tact and understanding for the sort of quiet, moody kid that a lot of films don’t treat with such respect,7 with almost every other character drawing out a different aspect of her personality in the spectacularly rich way that Ghibli always does so well.

There’s a lot to like in what I’ve seen from this year—three studios representing arguably the best of three massive mediums in animation, all putting out extremely strong efforts well after their broadly-acknowledged peaks in the 2000s. But if I had to recommend an animated film from 2015, When Marnie Was There would be a pretty easy pick. It’s not quite perfect, but it pulls off a level of depth that neither of the other two movies I’ve covered this year even attempt, and you’ve got to give it some credit for that.

Verdict: Better Animated Feature

Running Tally

2001: 2 better (2 nominated; 3 snubbed)

2002: 1 better (4 nominated; 0 snubbed)

2003: 1 better (2 nominated; 2 snubbed)

2004: 0 better (2 nominated; 1 snubbed)

2005: 2 better (2 nominated; 2 snubbed)

2006: 3 better (2 nominated; 2 snubbed)

2007: 3 better (2 nominated; 1 snubbed)

2008: 0 better (2 nominated; 0 snubbed)

2009: 2 better (4 nominated; 2 snubbed)

2010: 3 better (2 nominated; 4 snubbed)

2011: 1 better (4 nominated; 0 snubbed)

2012: 4 better (4 nominated; 1 snubbed)

2013: 2 better (4 nominated; 0 snubbed)

2014: 3 better (4 nominated; 1 snubbed)

2015: 2 better (4 nominated; 0 snubbed)

TOTAL: 29 better (44 nominated; 19 snubbed)

Join us in two weeks when…aw geez, we gotta talk about Zootopia.

Next: 2016 (4 nominated; 1 snubbed)

Essentially, the three actors (all of whom reprised their roles for the movie a decade later) all sat on a stage and read their lines into the audience.

Even then, you could just cast almost every part in the movie using one actor and a couple lookalikes and you’d be fine.

Hearing this in surround sound in our home theater was perhaps a top-five most awkward experience I’ve ever had in my life.

Though it’s worth noting that 2011 nominee Chico y Rita was left unrated despite including full frontal nudity

Inside Out 2 is obviously going to get a nomination and very likely the award, and The Wild Robot seems very likely to join the field as well. Beyond that…Moana 2 is hard to predict given Disney’s poor form recently, The Garfield Movie has been critically panned, Kung Fu Panda 4 was awful and should not receive any consideration, and Despicable Me 4 comes more than a decade after that franchise’s most recent nomination. That’s everything from the usual suspects, so there’ll probably be a good two or three picks from more avant-garde studios, and Aardman is always among the first names to come up in that category.

Editor’s note: please God do not give Despicable Me 4 a nomination, I beg of you. —Eli

Looking at you, Inside Out. How do you manage to not have the best-developed preteen girl in animated film this year when your premise is literally setting the movie inside her head?