Better Animated Feature: 2022

I don't think we've ever been this critical of Disney, which is really saying something...

This post may be too long for email. We recommend clicking through to the website for the best experience.

Eli: 2022 was a pretty shameful year for Disney. A lot of that is for reasons we’ll touch on in a minute, but just as much of it is for reasons that don’t even deserve to be discussed among the highest quality feature-length animation of the year. Pixar’s Lightyear was a bust, largely baffling audiences of all ages while gaining no cultural foothold. Disney Animation’s Strange World was immediately memory-holed and lost the studio some $200 million, earning its place in the Box Office Bomb Hall of Fame.

The other submissions that missed a nomination (like Minions: The Rise of Gru, barf) hardly feel worth mentioning here on account of how badly Disney pantsed themselves this year…so let’s just get into it.

The Nominees

Guillermo del Toro’s Pinocchio (won Best Animated Feature)

Marcel the Shell with Shoes On (nominated)

Puss in Boots: The Last Wish (nominated)

The Sea Beast (nominated)

Turning Red (nominated)

The “Best” Animated Feature: Guillermo del Toro’s Pinocchio

Eli: In theory, it should be pretty obvious that Pinocchio, the intellectual property, is not owned by Disney. The Disney movie was based on a book and many other movies have used the character or adapted the story, some of which predate the 1940 Disney film. The Shrek franchise has their own Pinocchio, there was an Italian live-action adaptation in 2019 that won a bunch of awards…the character has become more akin to a mythological creature than a storybook figure, each adaptation interpreting him in a moderately different fashion.

That said, if Disney has their hands on anything, their version is probably the one that first comes to mind for most of the general public. It’s a Disney Golden Age classic. So it was inevitable that, after the success of Maleficent (2014) spawned a seemingly endless stream of Disney live-action remakes, Pinocchio would eventually get the same treatment. Sure enough, on September 8, 2022, Disney’s live-action Pinocchio was born.

Thing is, though, it’s pretty much universally agreed upon that all of these live-action Disney remakes are among the most wretched, cynical films ever created, and Pinocchio is no exception. Disney didn’t even give it a theatrical release; it was just spat straight onto Disney+ to overwhelmingly negative reviews. It was such a strange own goal, making such a bad adaptation of an intellectual property that wasn’t even theirs and then releasing it straight to streaming at a tremendous monetary loss. It opened them up to a better creative team making a much better Pinocchio film and exposing the Disney film for the soulless product that it was.

That isn’t really what Guillermo del Toro set out to do with his version of Pinocchio, but it’s exactly what happened. Guillermo del Toro’s Pinocchio released in select theaters on November 9, 2022, and on Netflix a month later. Del Toro was notably a fan of the 1940 Disney adaptation and took lots of inspiration from its animation in creating his own, so his goal for this film wasn’t to make a better version than Disney did, but given how soon after the live-action remake Guillermo del Toro’s Pinocchio was released, the comparisons were unavoidable, and they were embarrassing for Disney.

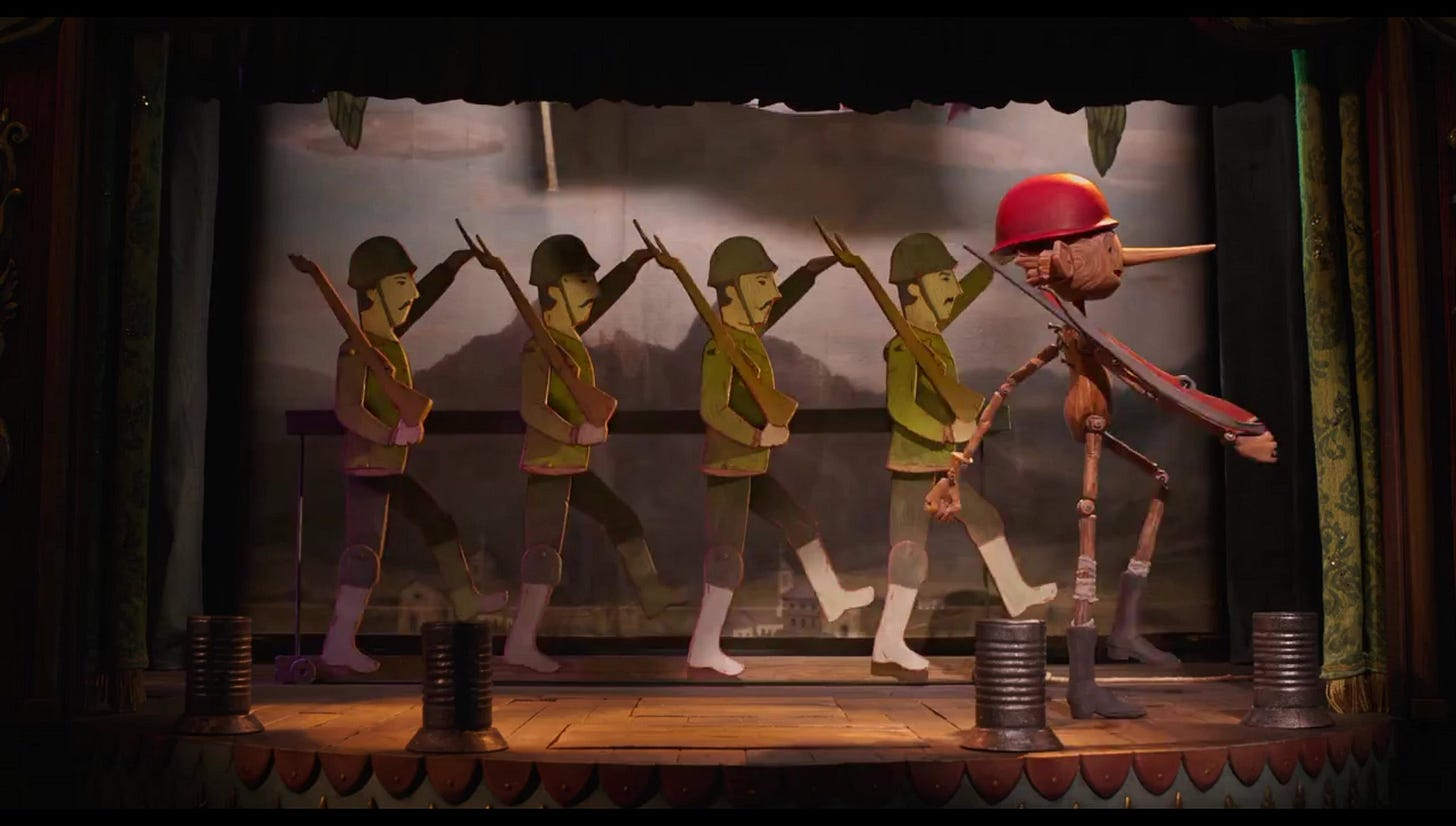

Alongside 2011’s Rango, Guillermo del Toro’s Pinocchio is the second movie to win Best Animated Feature from a director far more well known for their work in live action. Like Rango, it’s an unusually dark film for a BAF winner, featuring overt fascist imagery and war crimes that directly cause the death of a child. Somehow, despite that, it also doesn’t take itself too seriously. The titular character is the naively optimistic goofball most people associate with the character. Benito Mussolini is voiced by Tom Kenny. It’s a very nuanced movie, and while it obviously deserved to win Best Pinocchio Feature of 2022, the fact that it also won Best Animated Feature is a good thing for the industry.

Guillermo del Toro, one of the prestige directors in cinema, is also one of its biggest proponents of animation. In his acceptance speech for this award, he proclaimed: “Animation is cinema, animation is not a genre, and animation is ready to be taken to the next step. Keep animation in the conversation.” A few months later, he went even further and claimed that he was about ready to abandon live action and put all of his efforts into making animation a more respected medium: “Animation to me is the purest form of art, and it’s been kidnapped by a bunch of hoodlums. We have to rescue it. I think that we can Trojan-horse a lot of good shit into the animation world.”

After spilling hundreds of words on Disney’s Slop Era earlier this month, this is truly music to my ears, and it’s refreshing that Best Animated Feature went to a director who clearly cares about the medium beyond seeing it as a means to extract cash from kids.

Be that as it may, it doesn’t automatically make Guillermo del Toro’s Pinocchio the true best animated movie of 2022. How’d it fare against the other nominees?

The Other Animated Features

Marcel the Shell with Shoes On — Leah

Nominated

Marcel the Shell with Shoes On is a mockumentary about a little shell named Marcel who lives in an Airbnb with his grandmother and becomes a documentary subject for a guest staying there. Marcel and his grandmother have adapted to life on their own, as most of their community had gone missing. It’s difficult for Marcel, but he does his best to live a “good life” and not just “survive.” The movie shows Marcel becoming popular through the documentaries about him uploaded to YouTube, and him trying to use that to help find his missing family. He also has to deal with the reality of his grandmother’s deteriorating health.

Marcel is unique among BAF nominees in that it’s a film that uses both animation and live action prominently. Marcel is an animated character that interacts with a real-world environment and people played by actors. It ends up working really well in context, blending the fantastical with the mundane. Using a little fantasy creature like these walking, talking shells casts a different light on our world. Marcel’s viral success comes with some drawbacks, something that’s definitely relevant to today’s internet culture. I also think Marcel’s isolation from his community speaks to the difficulties of 21st century loneliness.

Pinocchio was quite a different viewing experience from Marcel. It’s a retelling of the familiar Pinocchio tale, set with a backdrop of fascist Italy. Marcel and Pinocchio both center on a kid with a very limited view of the world, but Marcel isn’t as obnoxious in his ignorance as Pinocchio. The two movies are also completely different in tone, with Pinocchio being more fantastical and larger, while Marcel focuses on a smaller-scale story in a more grounded setting.

Pinocchio is fully animated, using a CGI style that accentuates both the realism of 1930s Italy and the fantasy elements of the Pinocchio story. Meanwhile, again, Marcel is a live action/animation blend, making it a unique take on the medium. It takes creativity to pull off blending animation with live action, and Marcel deserves credit for making it work, drawing us into the way the shells live within our familiar world.

Pinocchio was a good movie, putting a unique spin on a classic tale with a distinct style and a solid narrative. I agree with Eli’s assessment above. However, to make a case for Marcel, it has a lot of creativity in its style and a more concise narrative that I personally found more compelling. As so many of these years do, I think this ultimately comes down to personal taste. The creativity and relevance of Marcel are enough for me to make a case for it as a:

Verdict: Better Animated Feature

Puss in Boots: The Last Wish — Eli

Nominated

Puss in Boots: The Last Wish is a movie so confoundingly good that I legitimately do not understand it.

It’s not the best movie I’ve ever seen or anything—though it is damn good—but after the complete mess that was Puss in Boots (2011), there were absolutely no expectations for this franchise to produce anything worthwhile. Subsequently, this movie took at least eight years to make and was delayed several times for several reasons, both creative and organizational. The script was rewritten. The project switched directors midway through production. At one point, they considered putting Shrek in the movie, which feels like something you’d only do if you were out of ideas. Everything on Earth was pointing to this movie being a failure.

Instead, DreamWorks gave us an instant classic that combined contemporary storybook-style animation with the mature, badass, comedic, and action-packed Puss we seemingly hadn’t seen since his debut in Shrek 2, a movie that had already become old enough to vote. Never before have I seen the second entry in an animated movie franchise surpass the first by such a wide margin. Not by Shrek 2, not by Kung Fu Panda 2, not even by Toy Story 2. Granted, this is more a byproduct of the original Puss in Boots being phenomenally bad rather than this sequel being otherworldly good, but still! This came out of nowhere!

The Last Wish joins our feline friend years after the events of the first movie, as he’s just lost his eighth of the nine lives every cat is born with. Usually fearless to the point of arrogance, Puss becomes genuinely terrified at the possibility of surrendering his final life and goes into hiding. Eventually, after a somewhat convoluted first act, Puss snaps out of his funk and sets out to find the fabled Wishing Star so he can earn its titular “last wish” and regain his other lives. He’s joined by Perrito, a happy-go-lucky Chihuahua he met in hiding, and Kitty Softpaws, his lover-turned-nemesis, who both also want to find the star for separate reasons. But hijinks ensue, as they’re far from the only ones on the hunt!

On the journey, The Last Wish touches on a cavalcade of morals relayed both through the visual lens of colorful, kid-friendly animation and through sharp, unmistakably adult writing. This movie routinely garners direct comparisons to Into the Spider-Verse for the art style, and it’s far from unique in this respect, but what pushes it closer to the genuine article than many other Spider-Verse-influenced projects are those storytelling beats. Very few children’s animation properties treat their audience as intelligently as The Last Wish does.

And that’s what puts this above Guillermo del Toro’s Pinocchio for me. The two films deal with very similar subject matters at their core, as both protagonists are tasked with extraordinarily heavy and humbling quests that both result in them learning to accept that life’s meaning comes primarily in its brevity. The difference is that, while Pinocchio does deal with adult topics—probably even more so than The Last Wish—it kinda keeps the kid gloves on while doing so, because you see just about everything through the perspective of a child.

The first act of Pinocchio is supremely annoying in this way. After being magicked to life, Pinocchio spends seemingly forever asking annoying questions and being immature and getting into sticky situations through his own naivete. It’s basic kid stuff, but it wears out its welcome far sooner than the film moves on from it, and jeez man, the movie is 117 minutes long. Why didn’t you cut any of this? Then, in the second act, Pinocchio is both forced into slavery and nearly shot by a friend point blank, but neither moment has any real stakes because the viewer understands that he’s immortal and physical threats mean nothing to him.

On the other hand, in The Last Wish, it is always crystal clear that any misstep from Puss will end his story for good, and the movie feels so much bigger for it. It’s incredible, and I can’t recommend it enough. Even if you haven’t seen the first one—in fact, forget about the first one entirely—Puss in Boots: The Last Wish is well worth your while.

Verdict: Better Animated Feature

The Sea Beast — Preston

Nominated

A prominent storyline in Western animation during the 2020s—arguably the most prominent storyline—has been Disney’s increasing refusal to allow anything interesting into the works they target at younger audiences. This trend is not limited to film; in two prominent, recent examples, the company cut two storylines about trans youth from its series Win or Lose (removing a scene that had already been planned and storyboarded) and Moon Girl and Devil Dinosaur (removing an entire episode after the production stage, when it was pretty much ready to air). As recently as Thursday, interviews with former Pixar employees suggested the studio’s upcoming film Hoppers had been instructed to walk back themes of environmentalism—which, relevant to this piece, may have also affected Turning Red, which aired trailers with scenes of the main characters protesting about environmental issues that were absent in the final cut of the film. And that example serves as a reminder that, for every case of Disney executives meddling in the creative process that’s obvious, there are likely far more that the company manages to hide, more or less.

This is all pretty depressing, particularly if you happen to be a prospective or current member of the animation industry, because…well, particularly when it comes to film, Disney is the only show in town for a lot of people. Other animated studios exist, of course, but there’s no denying that traditionally, if you want to be involved in a Western animated film that (a) will be seen by a lot of people and (b) can have some serious artistic merit, you go to either Disney Animation or Pixar. Now their parent company is sacrificing a huge chunk of column (b) to get a little more out of column (a), and given the historical state of Western animation, it sure feels like a crisis. Sure, other studios have always offered more artistic freedom given what Disney is by its nature, but the reason these two have accumulated such talent is simple—nobody’s ever come close to offering such a good tradeoff of those two factors. Now the deal’s getting worse, so…what are you supposed to do, if you want to tell a story that’s not afraid to be about something?

Well, the good news is, the historical state of Western animation is not the current state of Western animation. Lately, some big-name studios like Sony and DreamWorks have proven more willing to experiment with stylization and narrative depth; meanwhile, smaller studios have gained more and more of a foothold as the industry has expanded in general. Disney’s monopoly on talent has declined pretty significantly over the past few years, and those trends have led to a couple landmark moments in the last few years.

First: Disney lost back-to-back Best Animated Features. That’s wild! And it’s not like they haven’t put out anything good in that stretch…sure, Disney Animation hasn’t, but Pixar had a film in 2022 that definitely would’ve won (Turning Red) and another in 2023 that probably would’ve won (Elemental) in the environment of the 2000s or 2010s. It’s not just that the studios, or the expectations they’re built up with, have faltered; the competition has become a lot fiercer. 2022’s actual winner, Guillermo del Toro’s Pinnochio, is a perfect example of that fact—I doubt it would’ve won a decade earlier, prior to shifts in the way the Academy thinks about animation, but more importantly, I doubt it could’ve been made.

The same goes for The Sea Beast, to an even greater extent…and, in what I’ll admit is a pretty bizarre turn of events, I kinda have to give Netflix’s executives credit for handling animation somewhat well here. Obviously, they’re far from perfect—regardless of the medium, they seem willing and eager to cancel anything that doesn’t immediately reach spectacular ratings—but they do allow a pretty surprising amount of creative freedom. How they’ve handled the release and evaluation of their works is another matter, but by and large, it’s pretty clear Netflix doesn’t get involved mid-process to nearly the same extent as Disney.

The result is films like Pinnochio and especially The Sea Beast, which is particularly notable as maybe the most Pixar-esque film Netflix has overseen. So many things about this movie, from the character animation to the story beats to, yes, certain hallmarks of Disney’s creative limitations (e.g. no on-screen character deaths), feel very reminiscent of the recent Pixar canon. But that fact makes some of The Sea Beast’s other choices stand out quite a lot—in representation (two Black women among the four most prominent human roles), in violence (showing blood, showing main characters holding one another at gunpoint or knifepoint), and in theme (virtually using the British Empire as the main antagonists). The commitment to making it clear that this movie is for Pixar’s audience turns these details into statements: is there a good reason younger kids, tweens, and teenagers are never or rarely shown these things by the industry leader? And is it a good reason?

The Sea Beast is a solid film, but not a particularly great one. I like it, but it’s kinda made for me in a lot of ways—I mean, the pitch might as well have been How to Train Your Dragon meets The Pirates! Band of Misfits, which is a sure way to my heart. And even for me, it does feel a bit childish at times; certainly, they’re targeting the lower end of Pixar’s age range, with a relatively straightforward plot and a fair few narrative conveniences here and there. I like Pinnochio better, as a movie that I think does a clearly better job of reconciling young audiences with older ones, and I think it deserves to be seen as the forefront of the pushback against Disney from their growing list of major and minor competitors. But The Sea Beast is important to the story of animation, in its own way; it’s a pointed reminder that not every limitation Disney imposes for the sake of their target demographic is a good one. A children’s movie can show blood, and colonialism; a children’s movie can most certainly show Black people. They not only can—they should.

Verdict: Not a better animated feature

Turning Red — Preston

Nominated

So…hey, what actually happens when you refuse to allow yourself to make movies about as many topics as Disney has shut down lately? Often, the closest thing to a solution is to just try and draw from what’s worked in the past…sometimes to a very literal extent. During what Eli accurately deemed Disney Animation’s Slop Era in our last article, that studio has put out three sequels, all varying levels of soulless cash grabs piggybacking off prior success. I’ll admit to having not seen Frozen II, so I can’t really judge it in that regard, but Ralph Breaks the Internet definitely fits that description, and everything I’ve heard and seen about Moana 2 suggests it does as well. Pixar’s done much the same lately, too—going back a little further to 2016, they’ve released Finding Dory, Cars 3, Incredibles 2, Toy Story 4, Lightyear,1 and Inside Out 2, as many derivative works as fully original films.

Of course, when a sequel is unoriginal, it tends to be pretty glaringly apparent. Finding Dory earned the most flak of those Pixar films for copy-and-pasting the original movie’s plot with a few minor alterations, but most of these examples are guilty of at least a little direct imitation. But it takes even more blatant repetition for unoriginality to become apparent across different IPs…and I think that’s what bothers me about Coco, Encanto, and Turning Red, because come on. However well executed these films are, and they all are, they still tell almost exactly the same story with different coats of paint.

I think there’s probably a discussion to be had about one rather self-evident recurring element in these three movies—they’re all about deeply traditional families in cultures Disney hasn’t historically explored much, if at all. This is an unambiguously good thing when it comes to Coco, which firmly predates the other two and, at the time of its release, was mainly just a really good Pixar movie that happened to be set in Mexico (and embraced that fact well). But because the portrayal of culture in Coco was so widely acclaimed, and because these two films feel a bit derivative in so many ways, the fact that they pick out other cultures to portray with a very similar level and manner of strictness…arguably starts to verge on cultural appropriation on Disney’s part.

I’ll be the first to say I’m hardly qualified to delve into that topic, but I think it’s undeniably relevant in looking at a film which so heavily features the stereotype (however accurate it might be) of demanding, strict Chinese mothers. Turning Red is an improvement on Encanto in this regard—for one thing, it’s directed by Chinese-Canadian filmmaker Domee Shi, who can certainly speak to (and relate to) the cultural themes of this story better than Encanto directors Jared Bush and Byron Howard can speak to theirs. But for all the nonsensical criticism this film has received for merely attempting representation, more reasonable issues have also been raised from Asian perspectives about the clichés Turning Red leans into in those attempts. It’s at least a step above cultural appropriation because this story is actually by somebody who deeply understands the cultures they’re portraying, which is more than you can say for a lot of Disney films, but it’s arguably still far from perfect.

In any case, I think I’m within my rights to say that Turning Red’s portrayal of non-white culture doesn’t exactly feel bold. And that’s the problem with a lot of this movie, as fun as it is, and as strong as its emotional beats can be. Pixar’s entire brand is its inventiveness, and yet this movie feels like an attempt to coast on exactly the opposite, in a rather uncomfortably Disney Animation sort of way. The execution, the high-quality animation and sound design and voice acting (et cetera)—that’s what this film wants to set it apart from a lot of hackneyed stories by animation studios that aren’t Pixar. Without that layer of polish, this could so easily be a forgettable, 7/10 animated film that came out on Netflix and was forgotten immediately.23

This is the last Pixar film I’m reviewing for this series, at least as of the end of 2024. That’ll probably change in a few months’ time when we review the 2024 Oscars, where Inside Out 2 looks like a solid favorite to win BAF, but for now, this’ll be where I leave things with the most decorated studio in the award’s history. Even having argued that they should’ve lost five Best Animated Features that they won—and having never argued the opposite—I can safely say I agree with the Academy’s assessment that Pixar has no real comparison, nobody who’s ever truly matched them across 23 years of the BAF’s existence.

Whether that’ll remain true going forward is a different story. Pixar isn’t in a Slop Era; for all Turning Red’s faults, I’d still give it an 8/10 at the end of the day, and I still enjoyed it. But originality has definitely fallen a bit by the wayside for a studio that went through the entirety of the 2000s without so much as releasing a single sequel, and I hope it’s a trend that can be reversed. Pixar’s brilliance has always rested in its ability to tell new tales, to create spectacularly inventive worlds, and to do so without fear that some executive will force them to tear it all down and start again halfway through. Western animation will survive even if they lose that, true—but I hope they hold onto it. For as long as Pixar can still create stories that are so intrinsically and uniquely theirs, I want to keep watching.

Verdict: Not a better animated feature4

Running Tally

2001: 2 better (2 nominated; 3 snubbed)

2002: 1 better (4 nominated; 0 snubbed)

2003: 1 better (2 nominated; 2 snubbed)

2004: 0 better (2 nominated; 1 snubbed)

2005: 2 better (2 nominated; 2 snubbed)

2006: 3 better (2 nominated; 2 snubbed)

2007: 3 better (2 nominated; 1 snubbed)

2008: 0 better (2 nominated; 0 snubbed)

2009: 2 better (4 nominated; 2 snubbed)

2010: 3 better (2 nominated; 4 snubbed)

2011: 1 better (4 nominated; 0 snubbed)

2012: 4 better (4 nominated; 1 snubbed)

2013: 2 better (4 nominated; 0 snubbed)

2014: 3 better (4 nominated; 1 snubbed)

2015: 2 better (4 nominated; 0 snubbed)

2016: 5 better (4 nominated; 1 snubbed)

2017: 0 better (4 nominated; 0 snubbed)

2018: 0 better (4 nominated; 0 snubbed)

2019: 4 better (4 nominated; 0 snubbed)

2020: 2 better (4 nominated; 0 snubbed)

2021: 2 better (4 nominated; 0 snubbed)

2022: 2 better (4 nominated; 0 snubbed)

TOTAL: 44 better (72 nominated; 20 snubbed)

Are we getting too predictable? Well, next year—the most recent award to date—is a doozy! In a ridiculously stacked field, The Boy and the Heron gave Studio Ghibli its long overdue second win. We’ll talk 2023 and then return for 2024 after that winner is awarded in March.

Join us!

Next: 2023 (4 nominated; 0 snubbed)

A spin-off, not a sequel, but in the context of the studio trying to rehash old content, it definitely fits.

It’s not really a one-to-one comparison, but where my mind immediately went here was Next Gen (2018), which lacks a lot of the finishing touches that Turning Red has—but is, at its core, a similar story idea, decent but ultimately a bit trite. I think I might’ve rather seen Pixar run with Next Gen’s pitch and Netflix run with Turning Red’s, all else being equal.

Editor’s note: Where my mind immediately went was 2020’s Over the Moon, another Chinese coming-of-age story that released directly to Netflix, was pretty dull, and was forgotten immediately. –Eli

Editor’s note: Leah and I both would have declared this a Better Animated Feature pretty easily, for the record. Sometimes that’s just the way the cookie crumbles. —Eli

I haven't seen The Sea Beast, but out of the other four, I think I'd pick The Last Wish as my favorite.