You Have to Be Pretty Good to Be Really Bad: Strikeouts

They don't just let any scrub strike out 200 times.

I’ll start with a simple question: what’s the object of the game of baseball?

That’s right! To score more runs than your opponent.

How do you score runs? Well, you get on base, you move runners up, and you drive ‘em in. If the opposing pitcher is wild enough, it’s possible to accomplish this by doing absolutely nothing, but the overwhelming majority of runs scored require actually hitting the ball at some point in the process.

You have to make contact to get a base hit, and even if you don’t get a hit, there are clear benefits to putting the ball in play: if there are runners on base, you can move them up, and even if there aren’t, there’s still the off chance the defense botches the play and you reach on an error.

I spend so long explaining the fundamentals of baseball offense to say this: it stands to reason that among the very worst things you can do at the plate is to fail to hit the ball—to strike out.

Sure enough, for most of baseball history, a strikeout has been seen as a mark of embarrassment against the hitter. Even now, when they’re somewhat more accepted, they still hold no concrete value and are generally met with groans.

The logic should then also follow that the hitters who strike out the most are among the worst hitters in the sport.

But y’know what? You could make a more convincing case that the opposite is true, thanks to one of baseball’s longest-held secrets: you have to be pretty good to be really bad.

Let me explain.

You Have to Be Pretty Good to Strike Out 200 Times

From the birth of baseball to the present day, the strikeout has generally trended upward. When the National League debuted in 1876, teams struck out about once a game on average (1.13 times, to be precise). When Jackie Robinson integrated the game in 1947, that number was 3.07. In 2023, it was 8.61.1

Does that mean hitters are getting worse? In a relative sense…kinda. They’re worse at making contact with the ball than hitters were in the past. There have actually been more strikeouts than hits in every season since 2018, before which it had never happened once.

But that’s not for no reason. Pitchers today are collectively way nastier than they’ve ever been, and baseball as a whole has culturally become okay with substituting some contact for power.

They weren’t quite as okay with it in 2008, when Mark Reynolds of the Diamondbacks became the first hitter ever to strike out 200 times in a season. He was a laughingstock, and it didn’t help that he also committed 35 errors in the field, the most in the league by a desert mile.

Then he struck out 200 more times in 2009…

…and 200 more times in 2010. Geez, what is he, blind? He must have been one of the worst hitters alive!

Except he wasn’t.

And neither were any of the other hitters who’ve struck out 200 times in a season since then. It’s happened 19 times, and in 15 of them, the player who did it hit better than league average. Most of them significantly so.

Aaron Judge struck out 208 times in 2017. He was named the American League Rookie of the Year and probably should have been the MVP.

Chris Davis struck out 208 times in 2015. He led the majors with 47 homers.2

Joey Gallo struck out 213 times in 2021. He was named an All-Star, won a Gold Glove, and also walked 111 times to lead the American League. He even earned a midseason trade from the rebuilding Rangers to the contending Yankees.

However, not everyone enjoyed such success. Four players struck out at least 200 times while also hitting below league average. That hardly qualifies as “pretty good”, so why were they allowed to be “really bad”?

Let’s take a closer look and diagnose these four player-seasons.

Two of them were Mark Reynolds.

Mark Reynolds, 2008 and 2010

Chalk it up to sequencing. In 2008, he had a long leash as a young slugger in his first full season. Then he fulfilled that promise in 2009, hitting 44 homers and earning MVP votes despite striking out 223 times, the most ever in a single season. He resultantly got another long leash in 2010.

In both down years, he was still producing at just over 95% of league average with the bat, which is definitely enough to early you regular playing time if your career is still young. But the Diamondbacks had had enough of Reynolds after three consecutive 200-K seasons to begin his career, so they traded him to Baltimore after the 2010 season. Reynolds would stop the bleeding there, striking out a mere 196 times in 2011.3

Yoán Moncada, 2018

Yoán Moncada’s 2018 whiffs can also be explained by a team trying to let a prospect develop.

After the 2016 season, the White Sox entered a rebuild and shipped star pitcher Chris Sale up to Boston. Moncada, then rated the #2 prospect in baseball, was the key piece in the return for Chicago. He got injured in a collision midway through 2017, so 2018 was his first full season in the bigs. At age 23, he was clearly still adapting to major league pitching, but the White Sox were invested in letting him figure it out, so he struck out 217 times.

Drew Stubbs, 2011

In 2011, Drew Stubbs had easily the worst 200-K season of all time at the dish, hitting for a wRC+ of just 90.4 But even here, there’s a silver lining: the dude could run.

His 40 stolen bases were tied for second in the National League. And his 9.3% walk rate was also above league average, so even though he wasn’t making contact with the ball, he still got plenty of chances to show off the wheels. The Reds even led him off for most of the season despite the fact that he was striking out 30% of the time.

Which brings me to my point: the average 200-strikeout season sees its hitter strike out just under a third of the time. That’s unequivocally bad—among the worst qualified strikeout rates in baseball in every relevant season, if not the very worst. But plenty of bad hitters strike out at this rate and don’t get enough plate appearances to strike out 200 times because they don’t provide enough good to mitigate the bad.

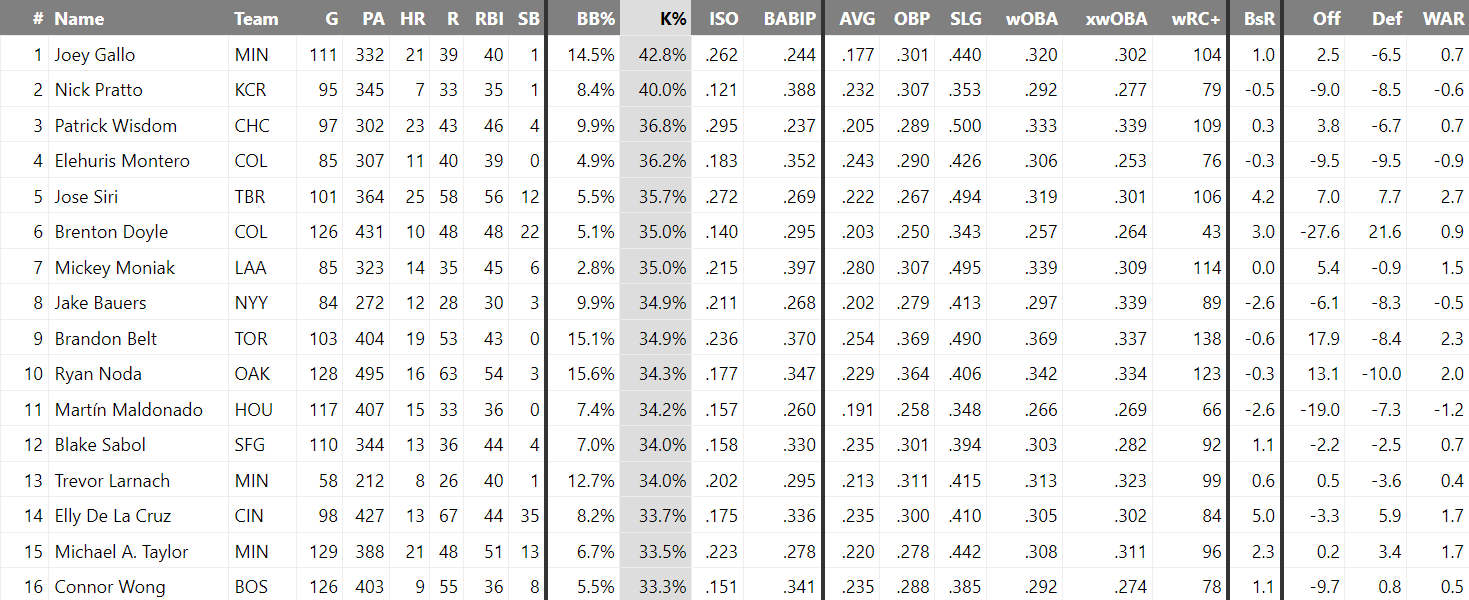

Here’s every player who took at least 200 plate appearances in 2023 while striking out at least a third of the time.

Most of these seasons were mediocre-to-bad at the plate. Some of them were horrendous in every aspect of the game. None of them struck out 200 times.

There’s no way Chris Carter or Eugenio Suárez or any of these other strikeout kings get to bat 600 times5 if they’re not bringing something to the table—power or speed or, at the very least, promise.

When a hitter strikes out 200 times in a season, they also (on average) crush 35 homers, walk 82 times, and hit 16% better than league average. Because you have to be pretty good to be really bad.

On an even broader scale, only two hitters have ever struck out more than 2500 times in their career: Reggie Jackson and Jim Thome. They’re both in the Hall of Fame.

What exactly is your point?

On the surface, this whole thing seems obvious, right? Of course the players who accrue the most counting stats also accrue the most negative counting stats. Baseball is a game of give and take. A game in which failing 60% of the time puts you up there with the best players in history.6 Everyone knows this.

But not everyone knows—or remembers—that this isn’t just baseball. It’s life.

Think of every time you’ve hurt someone you care about. Maybe you said something you didn’t mean or you accidentally forgot someone’s birthday. It’s not just you. Everyone does it all the time.

If that person doesn’t care for you, there’s a good chance they become fed up with you and remove you from their life before too long. No one wants to waste their time with people they don’t like.

But some people, either immediately or eventually, look past it. They recognize that nobody is perfect and elect to move on from your mistake. In keeping you in their life, they give you another chance to hurt them.

They do this, of course, because they like you. Why do they like you even though you’ve just hurt them? Maybe you go out of your way to pick them up when they’re down. Maybe you see value in them when they don’t even see it in themself. Whatever it is, you’re doing something right.

So they keep allowing you to hurt them, sometimes in ways neither of you had ever considered possible.

And you hurt them over and over and over again.

You never mean to, but you’re human and you can’t stop yourself.

Sooner or later you’ve hurt them 200 times.

But they’re still with you. They cut most people from their life after a handful of infractions. They gave some others a few dozen transgressions before deciding enough was enough. But they still haven’t let go of you.

This is what it means to love someone. To believe in them and understand that no matter what bad things might happen, the pros still far outweigh the cons. Every rose has its thorn. Every hit has its strikeout.

It’s nearly impossible to hurt someone who doesn’t love you to the extent that you can hurt someone who does. And if you try to name the people who’ve hurt you the most through the years, you’re probably also naming the very most important people in your life.

But you still love them. Because, metaphorically speaking, they drive in more than enough runs to balance out a few extra strikeouts.

If you’re ever worrying about how often you hurt someone you love, just remember that this feeling also applies to you. You’ve hit plenty of home runs in their life. They’ll tolerate the strikeouts.

You have to be pretty good to be really bad.

That was super heavy. Can we talk about baseball some more?

I thought you’d never ask.

Strikeouts aren’t the only negative outcome that causes baseball players so much scorn. Over the next few weeks, I’ll highlight four more negative counting stats for which the most prolific compilers are significantly better players than you might expect: two more for batters and then two for pitchers.

None of these other pieces will have an emotional life lesson at the end. It’s just gonna be me geeking out over outliers and oddities of baseball’s past.

I actually did most of the research for these pieces last summer (for reasons that will become clear in the next piece) and have been sitting on it for about six months, so I can’t wait to share the rest of it with you!

Next up, finish the equation: 6 - 4 - 3 =

Chapter 1: Strikeouts

Chapter 2: Double plays

Chapter 3: Caught stealing(s?)

Chapter 4: Walks

Chapter 5: Hits

The record is 8.81, set in 2019 when it became clear early in the season that the ball was very obviously juiced, so hitters adjusted their approach to swing for more power. The leaguewide slugging percentage that year was .435, second only to the .437 mark set in 2000 at the height of the steroid era.

If I can impart one non-essential thing on you through this piece: remember Davis for this season and for the 2013 season when he led the majors with 53 homers and hit for a 1.004 OPS (and just avoided this list with 199 strikeouts). Forget the hitless streak.

I like Mark Reynolds, I swear. The Rockies are my “National League team” and I have super fond memories of watching him hit balls to Wyoming on the fun teams of the late ‘10s. He just struck out a lot.

This is about the same production as the average catcher, the least offensively valuable position on the field. Stubbs was a center fielder.

Or 720 times if you’re the 2023 Phillies. The 12 apostles weren’t this faithful.

On offense, that is. If you are a pitcher and you fail 60% of the time, you are having a bad problem and you will not go to the Hall of Fame today.

This has the honor of being the only TLM article to make me tear up

teoscar hernandez mention (this is not a good thing in this instance)

Also, those last few paragraphs were BEAUTIFUL