You Have to Be Pretty Good to Be Really Bad: Hits

Get ready to learn more old-timey baseball, buddy

The pitching portion of this series is a land of extremes.

As I mentioned in the last chapter, the two primary methods of reaching base are by drawing a walk or getting a knock. If you’re going to be an effective pitcher, it stands to reason that allowing a ton of one requires preventing a ton of the other.

That last chapter discussed the “many walks, no hits” yin, fixating on Nolan Ryan—the most effectively wild pitcher in the history of the sport—and others like him. This fifth and final chapter will discuss the “no walks, many hits” yang.

As with the other end of the spectrum, this one is almost necessarily restricted to the olden days, relatively speaking. I briefly mentioned this in a chart caption all the way back in Chapter 1, but hits have remained pretty stable throughout baseball history; there’s been a slight downward trend, but since the sport has escaped infancy, almost every season has seen somewhere between 8.00 and 10.00 hits per team per game.1 Resultantly, the pitcher-seasons with the most hits allowed are all going to be those with a ton of innings pitched, and you just don’t see that today.

Without further ado, let the hit parade begin.

You Have to Be Pretty Good to Allow 300 Hits

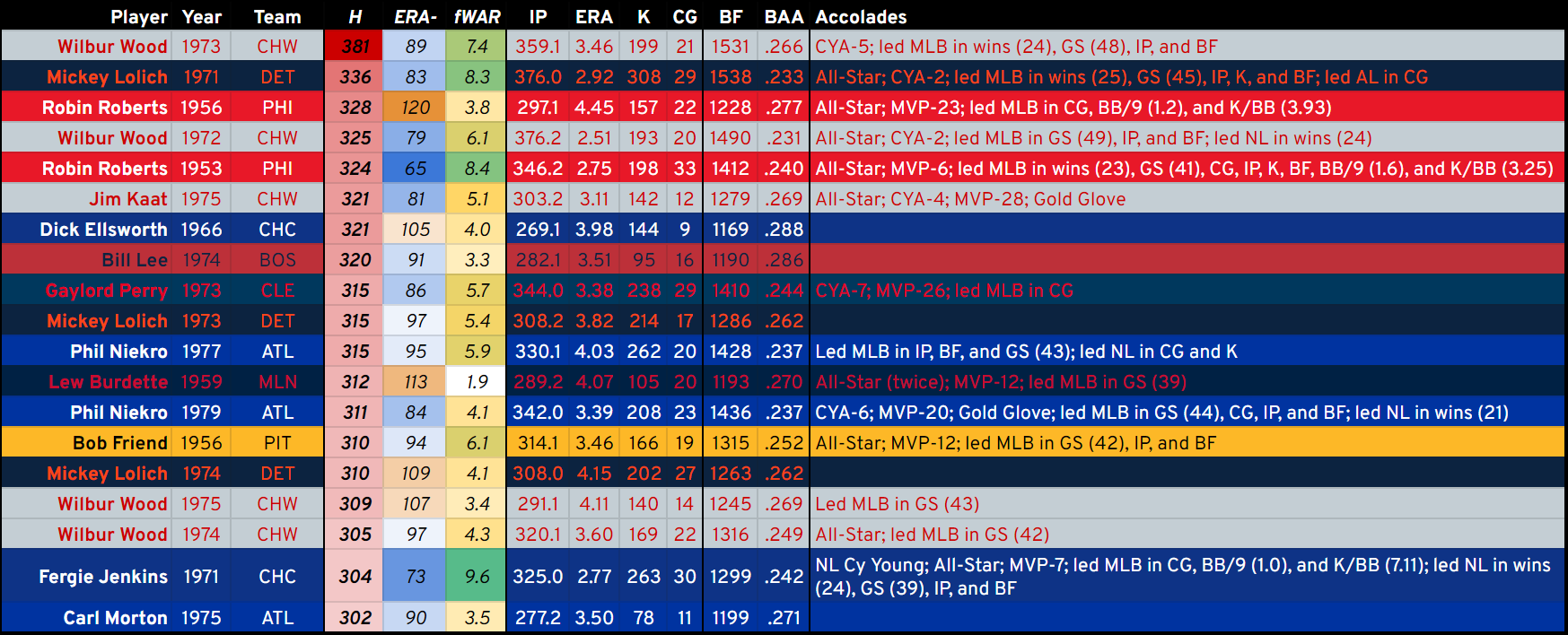

Since integration, there have been 19 pitcher-seasons that included at least 300 hits.

As usual, most of these seasons are excellent. We’ve got one Cy Young (1971 Fergie Jenkins) and another season that certainly would have been a Cy Young if the award existed at the time (1953 Robin Roberts). We’ve got a bunch of MVP votes. We’ve got a lot of wins (a thing people cared about at the time) and a whole ton of complete games.

What we don’t have are walks.

The lack of walks here isn’t quite as stark as the lack of hits was in the previous chapter, but it’s still noticeable. Jenkins and Roberts both led baseball in fewest walks per nine innings (BB/9) during their masterpiece seasons, and Roberts even did it again three years later when the rest of his stats were horrendous.

To emphasize this dichotomy, let’s begin looking at the five pitcher-seasons on this list with a below-average ERA-. You might have noticed that one of them comes from a team we discussed last time.

Mickey Lolich, 1974 Tigers

The 1974 Tigers are the only team since integration for which one pitcher allowed 150 walks and another pitcher allowed 300 hits. Their 150-walk hurler was Joe Coleman, owner of the worst 150-walk season since integration by ERA-. Coleman gave up 158 walks and 272 hits.

Their 300-hit arm belonged to Mickey Lolich, who allowed 310 hits and just 78 walks. The reason Lolich got this opportunity is obvious if you look at the rest of the table: he’d pitched effectively in each of the previous three seasons despite also allowing at least 300 hits in two of them.

In 1971, Lolich led baseball in a whole bunch of pitching stats—including hits allowed—thanks in large part to his absurd volume of 376.0 innings pitched. He was an All-Star and finished second in the AL Cy Young voting.

This was followed by another All-Star appearance and top-three Cy Young finish while allowing a pedestrian 282 hits in 1972, then a reasonably above-average but not jaw-dropping 1973 in which he allowed 315 hits.

By 1974, his 33-year-old left arm had probably had enough and his performance cratered. In 308.0 innings, Lolich led baseball in earned runs (142) and homers allowed (38), a far cry from the more enviable strikeout and win crowns that almost netted him a Cy Young in 1971.

That 1971 AL Cy Young race was a barnburner. Lolich had easily the most impressive volume, but voters sided with the better rate stats and superior team performance of Oakland’s Vida Blue. And there’s an argument to be made that the award should have gone to someone else entirely.

Wilbur Wood, 1975 White Sox

Wilbur Wood had a rather eventful career.

Born and raised in Greater Boston, Wood was a multi-sport star in high school who drew absurd amounts of interest for several sports from colleges nationwide. In 1960, just as he was set to graduate, his local Red Sox offered him a big signing bonus because they thought it would make them look good in the press. Wood happily accepted and the Red Sox called him up to the majors the next year, at age 19, because their attendance had cratered following the retirement of Ted Williams.

After a few mediocre years spent bouncing around between the majors (where he was pretty bad) and the upper minors (where he was really good), Boston cut bait with him in 1964 and Pittsburgh bought his contract. He pitched decently in relief for the 1965 Pirates, but he didn’t make the team out of Spring Training in 1966, at which point the 24-year-old Wood thought about quitting baseball entirely.

Encouraged by his wife, he instead gave it one last chance and reported to the Triple-A Columbus Jets. As usual, he dominated, but the Pirates still refused to promote him. At the end of the year, the White Sox went out of their way to acquire him and invite him to 1967 Spring Training. There, Wood met bullpen anchor and knuckleballer Hoyt Wilhelm, who at age 44 was beginning the 16th season of a 21-year career that would eventually land him in the Hall of Fame.

Wilhelm taught Wood the knuckler, Wood broke camp with the White Sox, and the rest is history. Wood immediately became a mainstay in the White Sox bullpen, first as a long reliever who occasionally made spot starts and then as a late-inning fireman who racked up 52 saves from 1968–1970 (that was a lot back then).

Which brings us back to 1971. Wilbur Wood was set to begin yet another year as a key bullpen arm for the White Sox, but fate had other plans: starting pitcher Joe Horlen broke his leg on the last day of Spring Training and manager Chuck Tanner tabbed Wood to replace him in the rotation. Wood, whose previous career high in innings was 159.0, responded by tossing 334.0 innings to a ridiculous 1.91 ERA for an ERA- of 53. That was lower than Vida Blue’s 56 and far lower than Mickey Lolich’s 83, which arguably should have made him a Cy Young contender, but he only netted one out of 24 first place votes and finished third in the voting.

After that masterpiece 1971 season, Wood became perhaps the most absurd workhorse the sport has ever seen. In 1972, he pitched 376.2 innings, which is a major league record not just in the integration era but even in the live ball era (since 1920). After another 359.1 innings in 1973, he lowered his workload to 320.1 innings in 1974 and 291.1 innings in 1975.

In each of these seasons, Wood allowed at least 300 hits—in 1973, the number was 381, which is the live ball era record by a mile. In ‘72, ‘73, and ‘74, Wood’s production was still good-to-great. In 1975, it wasn’t. But it should be clear why he got the leash he did.

At least the 1975 White Sox also let Jim Kaat allow 321 hits in 303.2 innings while pitching well above average.

Lew Burdette, 1959 Braves

Some of the most interesting careers of this era—if not all of baseball history—are drawn to this list as if through magnetic force.

Lew Burdette was originally signed by the Yankees but, after just 1.1 innings across two major league appearances in 1950, they traded him to the Braves. The Braves played in Boston at the time and moved to Milwaukee prior to the 1953 season, and it was here where Burdette would get his revenge.

After leading the National League in ERA (2.70) and all of baseball in shutouts (6) in 1956, Burdette earned his first All-Star nod in 1957 en route to his Milwaukee nine reaching the World Series, where they faced his former team.

In that series, Burdette was tabbed as the Braves’ #2 starter behind Cy Young winner Warren Spahn. He pitched a two-run complete game to win Game 2, then followed that up with a complete game shutout to carry Milwaukee to a 1-0 Game 5 victory and a 3-2 series lead. The Yankees won Game 6 to set up a do-or-die showdown between Warren Spahn and former World Series perfect game thrower Don Larsen, but Spahn got the flu and couldn’t go. Manager Fred Haney turned to Burdette on two days’ rest and, in another episode of “they don’t make ‘em like this anymore”, Burdette threw another complete game shutout as the Braves won the clincher 5-0. World Series MVP.

To follow this up, Burdette pitched even better in 1958, but he and Spahn split Cy Young votes and the hardware went to the Yankees’ Bob Turley.2 And that catches us up to 1959.

In 1959, Burdette threw a career-high 289.2 innings. When he was on, he was really on; he led the National League in shutouts (four) and also in wins (21, thanks in large part to Milwaukee’s Henry Aaron-led offense).

On May 26 against the Pirates, Burdette opposed one of the most infamous pitching performances in history. Harvey Haddix took a perfect game into the 13th inning before Milwaukee’s leadoff batter reached on an error, followed by a sac bunt and an intentional walk to Aaron. With two runners on base but the extra long no-hitter still intact, Joe Adcock hit what should have been a walk-off three-run homer, but in his excitement, he passed Aaron on the basepaths, rendering him out. The hit was reduced to a double but the game was still over. Harvey Haddix had lost, 1-0. The win went to Burdette, who allowed 12 hits but heroically kept Pittsburgh off the board for all 13 innings to earn the complete game shutout.3

But when Burdette didn’t have it, boy was he bad; he led the majors in earned runs allowed (131), home runs allowed (38), and—of course—hits (312).

This volatility led to a pretty hilarious distinction: despite 1959 being, in aggregate, the worst full season of Burdette’s career by almost every measure, the highs were high enough that he was named an All-Star…twice. From 1959–1962, MLB played two All-Star Games per season. Burdette was selected to both 1959 contests. And you thought Alcides Escobar was undeserving in 2015.

Dick Ellsworth, 1966 Cubs

Dick Ellsworth is another classic case of early promise begetting a lot of second chances.

Highly touted when he graduated high school in 1958, Ellsworth was signed by the Cubs and almost immediately boosted all the way to the majors, where he debuted at age 18. He only lasted 2.1 innings in his debut and was quickly demoted to the minors, where he stayed for the next year and a half. After two good-not-great seasons in 1960 and ‘61, the bottom fell out in ‘62 and Ellsworth pitched to a horrendous 5.09 ERA (124 ERA-) and lost 20 games.

Their faith in him unwavering, the Cubs threw Ellsworth right back out there in 1963 and he rewarded them handsomely. In 290.2 innings, his 2.11 ERA was second in the National League only to Cy Young winner Sandy Koufax, and his park-adjusted 61 ERA- was even lower than Koufax’s 62.

Then Ellsworth had a 102 ERA- in 1964.

Then he had a 104 ERA- in 1965.

Then he had a 105 ERA- in 1966 while allowing 321 hits and losing a career-high 22 games.

It was only after that last season that the Cubs lost all hope and traded him to the Phillies.

Robin Roberts, 1956 Phillies

If you’re not up on your baseball history, there’s a good chance Robin Roberts is the best pitcher you’ve never heard of. He’s certainly the most impactful.

From his debut in 1948 through his age-28 season in 1955, Roberts threw 2311.0 innings at a rate about 30% better than league average. From 1951–1955, Roberts threw at least 305.0 innings in every season, leading the majors in innings each year. Today, we would marvel at how he led the majors in walks per nine innings and strikeouts per walk in 1952, ‘53, and ‘54. Back then, they gawked at the MLB-leading win totals every year from ‘52 through ‘55.

After the 1961 season, when Roberts was well past his prime, the Phillies sold his contract to the Yankees. Both teams played Spring Training in Florida, so Roberts got to face his longtime squad before playing a single regular season game for anyone else. To honor him, the Phillies—who had never retired any numbers at that point—retired Roberts’ #36 even though he was still actively playing baseball, which…basically never happens. In 1966, as Roberts’ career was winding down, the Cubs took a flyer on him and gave him his lucky #36. On August 16 of that year, he returned to Philadelphia to face the Phillies while wearing his own retired number. Of all the flexes that have ever been flexed in the history of the world, this is easily in the top percentile.

Aside from being named to the All-Star Game every year without fail, Roberts didn’t win any major awards for his masterful early-career seasons. Despite being clearly the best pitcher in baseball on multiple occasions and probably the best player in baseball on at least one, Roberts was routinely snubbed from the MVP Award, which writers were hesitant to give to pitchers.

Almost directly as a result of this, Commissioner Ford C. Frick introduced an award just for pitchers so that they could get the respect they deserved. The Cy Young Award was born.

Naturally, the year the award debuted was the year Roberts finally faltered. After consistently running an ERA- in or around the 70s for his whole career to date, 1956 Robin Roberts pitched to a frankly bad 120 ERA- and allowed an MLB-leading 147 earned runs. This was also the year he allowed his career-high 328 hits.

Roberts, of course, did not win the Cy Young that year,4 and he unfortunately never recovered enough to contend for it in any other year.

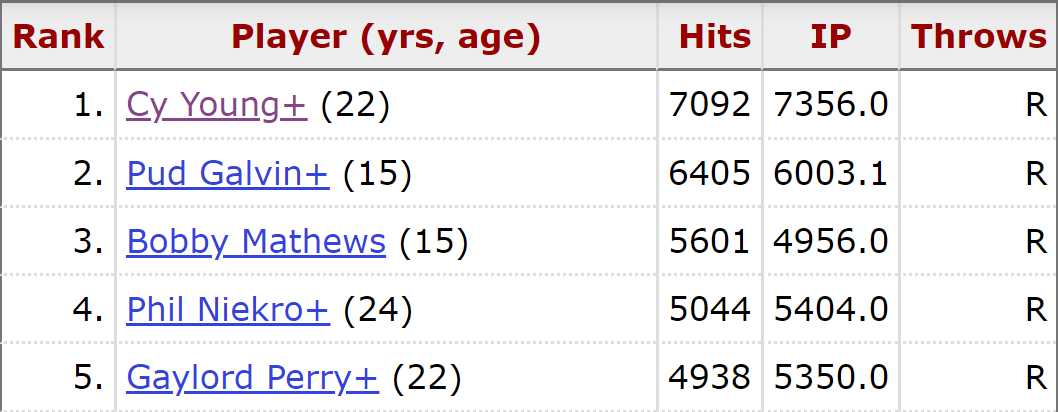

That name, Cy Young, has appeared in this piece as much as any other. As the man whose name graces the award reserved for the best pitcher in each league, “Cy Young” has become baseball shorthand for “world class pitching”. Young himself earned that distinction by dominating the sport’s pioneering days and setting a bunch of unbreakable records: 511 wins, 7,356.0 innings pitched, 749 complete games, the list goes on.

And on that list, as you may have guessed by now: 7,092 hits allowed.

Of course, Young pitched in the dead ball era, which I ignored in putting together this list, otherwise 13 of his seasons would have qualified. But even if we restrict to post-integration players, the two with the most hits allowed—Phil Niekro and Gaylord Perry—are still in the Hall of Fame.

Because, one more time for the folks in the back: you have to be pretty good to be really bad.

Thanks for reading.

Chapter 1: Strikeouts

Chapter 2: Double plays

Chapter 3: Caught stealing(s?)

Chapter 4: Walks

Chapter 5: Hits

The most recent season in which this was not true was 1968, the infamous Year of the Pitcher, which was so ridiculously imbalanced in their favor that MLB shortened the mound and shrunk the strike zone immediately after it was complete. That season saw 7.91 hits per team per game.

The next most recent season, and the most recent season on the other end of the range, was 1930, when teams earned an average of 10.15 hits per game.

These are the only two seasons since 1900 that fall outside of the 8-10 range.

Between 1956 (the award’s first season) and 1966, only one Cy Young was awarded across both major leagues.

According to SABR’s bio on Burdette, he called Haddix after the game to console him.

“You deserved to win, but I scattered all my hits and you bunched your one.”

Haddix hung up on him.

Don Newcombe did. The first Cy Young Award was won by a former Negro Leaguer.